Photo – © Broadway.com.

War Horse

Written by Nick Stafford, adapted from the novel by Michael Morpurgo

Directed by Marianne Elliott & Tom Morris

A review by Kathi E. B. Ellis.

Entire contents are copyright © 2013 Kathi E. B. Ellis. All rights reserved.

Tuesday, November 19, The Kentucky Center for the Performing Arts celebrated its Thirtieth Anniversary – to the day, as Broadway in Louisville’s Brad Broecker emphasized – with the opening night of the Louisville leg of the national tour of War Horse. From former Kentucky Governors to current Kentucky Center board members, and a champagne toast during the intermission, opening night was spectacular.

War Horse is a National Theatre, London, production that is now touring in several countries. In 2011 it won five Tony awards for the Broadway version, and it has been touring the U.S. since 2012. From the earliest stage of its conception, War Horse has been an international affair, with South African Handspring Puppets joining British theatre artists to create the highly imagistic world of Joey the horse.

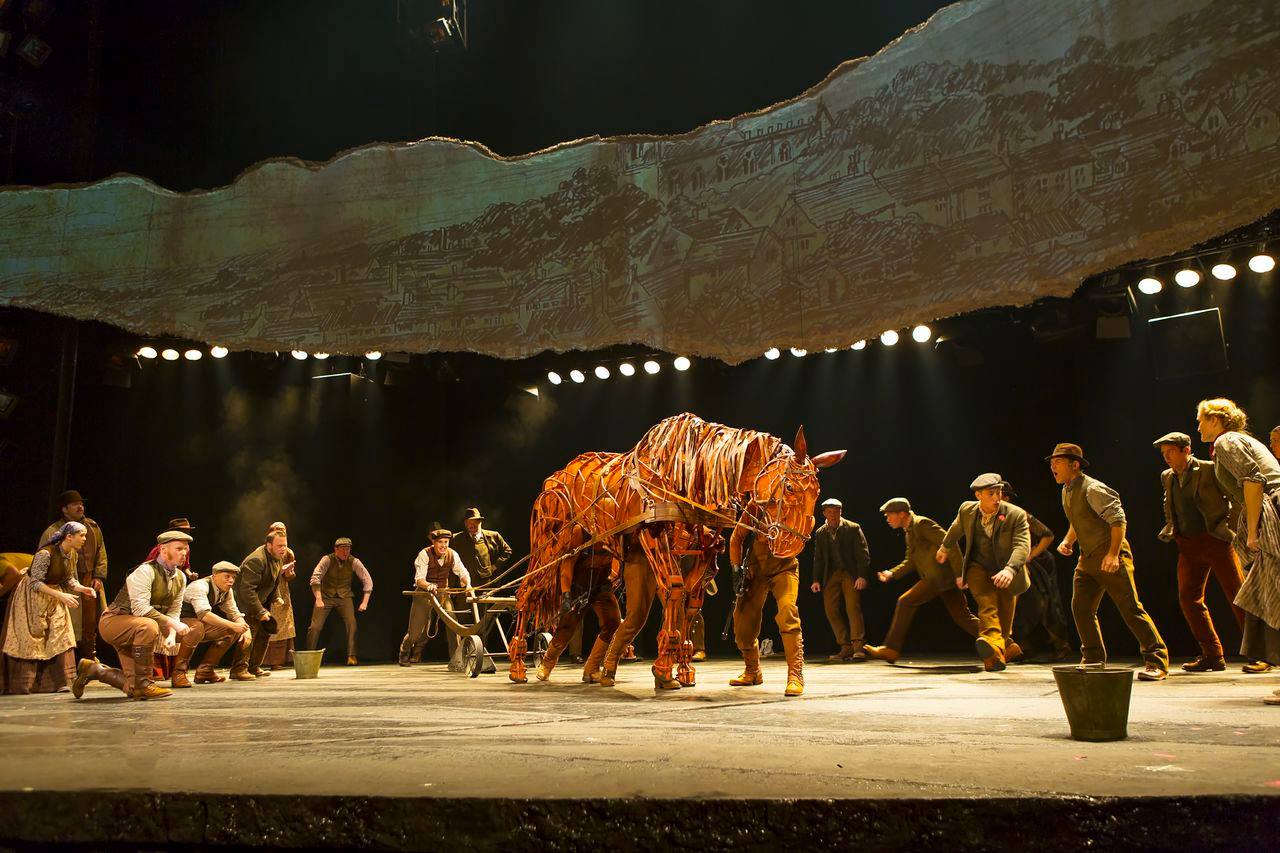

Based on the novel by Michael Morpurgo, War Horse is a journey of a horse and a boy from pre-World War I rural England, through the horrors of the first modern war, back to an England ever-changed by the “war to end all wars.” This world is created through theatrical techniques that exude sophistication and simplicity in equal measure. All of the theatricality is entirely transparent and in plain sight, enhancing the integration of puppets and puppeteers into a constructed world. Original co-directors Marianne Elliott and Tom Morris (current U.S. tour directed by another NT directed by Bijan Sheibani) are working on a huge canvas and ask the audience to suspend disbelief and engage their imagination with great effectiveness.

From the first moments of absolute darkness through which the audience members begin to glimpse a lone sketch artist, follow the strokes in his sketchbook – which come alive on a fragment of parchment suspended across the stage – and discern the haunting folk melody that emanates from the assembled company, who come into view as if the sun is rising, we are catapulted into a world at once recognizable and also highly artificial. The fences of the horse auction are mere lengths of fencing that do not touch the stage, suspended unobtrusively by the locals watching the auction; the boat that takes the soldiers and horses to France is suggested with metal railings that toss with the roughness of the Channel; the tank of the later war years is also, essentially, a puppet constructed so that the audience sees its framework and the actors who move it menacingly into a space that once was safe for the horses.

Paule Constable’s original lighting (adapted by Karen Spahn) is a key element to the evocation of this world. As audiences quickly foreground the horses over their manipulators, so the racks of lighting instruments in full view “disappear” as we move from interior to exterior, day to night, peace to war, and more – all suggested with lighting effects that are subtle and strong. The chiaroscuro approach picks out characters, seamlessly shaping the next step of the story. The quality of lighting emphasizes the shift from a bucolic existence into the harshness and instability of war. This shift is also exemplified in Scenic Designer Rae Smith’s “sketchbook” scenic element. Standing in for the lieutenant’s sketchbook, with the projections executed by 59 Productions, this floating banner begins with sweeping easy lines of the English countryside and moves into more detailed sketches of the town; as we move into battle, pencil gives way to charcoal and the lines become angular, anguished. In one exquisite sequence, the only time color is used is when splotches of blood transform into the universal symbol of memorial – poppies.

The musical world (music Adrian Sutton, song maker John Tams) defines the period through a deft combination of period songs with original compositions that echo the folk melodies of the time to underscore specific characters and themes in this story. There is also orchestral music that swells to a cacophony of war in chilling counterpoint to the traditional music of the period. Sound designer Christopher Shutt interweaves ambient country sounds and the ominous sounds of war in the aural world of the production. Both aspects of the aural world complement each other. Together with all design aspects, this production is one of the most effectively integrated shows I’ve seen, balancing twenty-first century technology with the aesthetic of a previous century.

Earlier this year, the War Horse tour brought Joey and a team of three puppeteers to Louisville for a sneak preview with Broadway subscribers and press. After delighting that audience with some fancy moves and coy advances, the puppeteers spoke about their work together. The puppeteers are drawn from a wide variety of actors, dancers, and those with previous puppet experience who then learn to work together to create the authentic movement and sound of the horses. The sounds, for example, are frequently made by all three puppeteers, beginning with one, traveling to a second, and resolving with the third; in part this is because a horse’s lungs are much bigger than those of a human, so this technique creates a large enough sound. The movements of the ears and tail are operated independently of the legs and head, this stroke of verisimilitude alone creating recognizable behavior for the audience. With a young Joey, a full-grown Joey, Topthorn and two other horses operated by two puppeteers, a large number of company members rotate through manipulating the horses as primary and understudy puppeteers. Others manipulate the high-soaring birds and the aggressive farm goose. The fact that so many of the company are part of the puppeteering as well as the hard-working ensemble brings a unity of purpose to the production that serves to heighten the particularity of Joey’s world.

The production is truly about ensemble and, as such, identifying individual performers is challenging. They all play multiple roles within a given performance and shift from role to role in different performances. I will make two exceptions and mention the singer (John Milosich) and musician (Spiff Wiegand) whom I saw on Tuesday; their poignant, plaintive songs were captivating. Their function is more individualized than other company members within the story as the songs create a light narrative thread and an emotional compass for the story. Tuesday night’s puppeteers for Joey were Mairi Bibb, Catherine Gowl, Nick Lamedica (foal), and Jon Hoche, Brian Robert Burns, Jessica Krueger (adult); and for Topthorn, Danny Yoerges, Patrick Osteen, Dayna Tietzen. The audience appreciated being able to recognize them as individual performers during the curtain call as well as puppeteers when the adult Joey and Topthorn also took their curtain calls.

November and December are months in which Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS make a call for donations at NY and touring shows. At the end of this week’s performances, one of the company will ask the audience to make donations, and they have some enticing show-specific premiums on offer! One way of showing your appreciation for Joey and his production is a donation at the amount you can afford.

War Horse

November 19 – 24, 2013

PNC Broadway in Louisville

TheKentucky Center

501 West Main Street

Louisville, KY, 40202

502-589-7777

http://louisville.broadway.com/