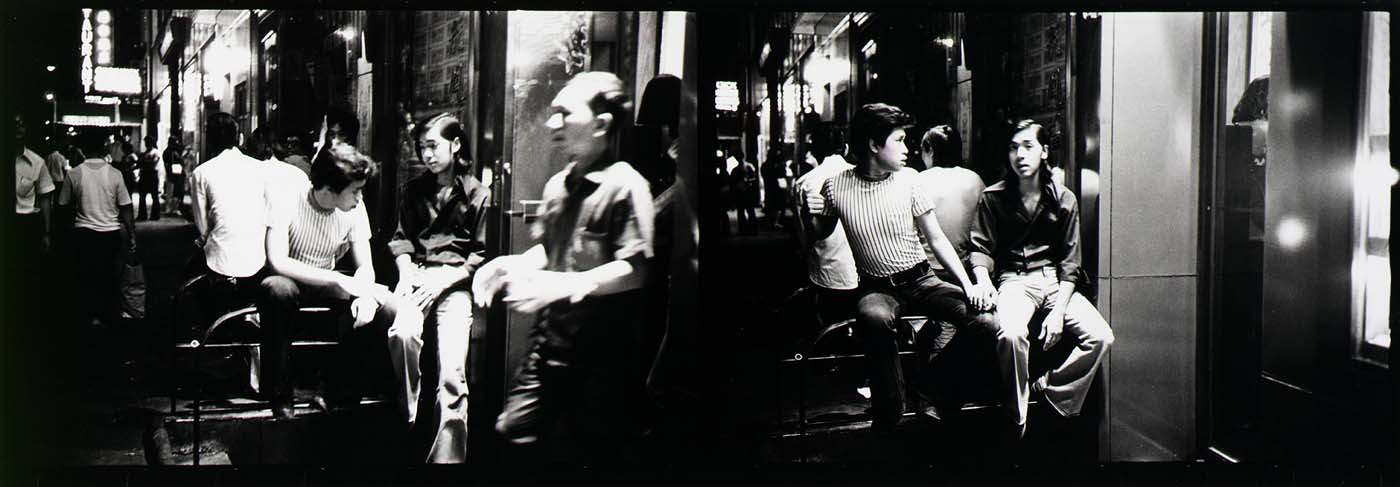

Eve Sonneman, “Night on Mott,” gelatin silver diptych, 1971

In the second of a series about the role of critical observation in the Louisville arts community, we hear from a BFA candidate attending a local institution of higher learning:

By Aaron Storm

Entire contents copyright © 2018 Aaron Storm. All rights reserved.

Right now, criticism gets a bad rap. Which, at first glance, seems reasonable: between the current political and cultural climates, the negativity permeating the air is palpable. Allegations of misconduct, abuse, and corruption have become commonplace, saturating our consumption of media, visual and otherwise.

In comparison, criticism of visual culture can seem insignificant, unnecessary, and overly harsh. Oftentimes, in those willing to concede that criticism has a role in contemporary local arts scenes, it is seen as a bitter pill to swallow. In such a rampantly unpleasant climate, why pile on the unpleasantries? In moments like these, shouldn’t we rely on the unfettered spirit of the artist to pour itself out freely, guiding and defining local culture?

Well, no.

This view of criticism, as the bitter pill, as a personal affront, or as blatantly unnecessary calls for a fundamental reframing of the way we engage with visual culture. Criticism is not an outdated and aggressive mode of interacting with art, but rather the most loving. Criticism takes a long, unflinching look at art, both situationally and as a whole, takes in all the good, and all of the bad and says “Great. What can we do to make this better?”

Standing in the gallery of Paul Paletti, local photo collector, and attorney, Paletti challenged me to find one thing I loved and one thing I hated on the walls, specifying that I should be able to defend each position.

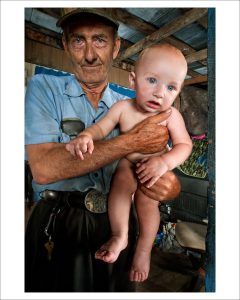

Shelby Lee Adams, “Lloyd Deane and Great Grand Baby,” 2010

I loved Eve Sonneman’s “Night on Mott,” a small, unassuming gelatin silver diptych from 1971 that had been printed with great dexterity and made clever use of time as a compositional technique. The geometrically divided interior, rich dark tones, and movement of the figures throughout the picture plane result in a complex composition that feels like a cohesive space at one time, rather than the same space represented twice. Subtle, virtuosic, intimate, and richly emotional, with themes of androgyny and homoeroticism, “Night on Mott” struck a chord.

In contrast, I hated the main show in the space, wherein renowned photographer Shelby Lee Adams seems to abandon the formidable compositional sensibility found in his black and white work for the full color, hyper-saturated kitsch one might find on the cover of an “Introduction to Photoshop” guide from 2008. The centerpiece of the body of work, “Lloyd Dean with Great Grand Baby,” especially seems to lack the comfortability that has become such a hallmark of Adams’ work in representing Appalachian families. This discord stems perhaps in part from the presentation: images steeped in rural specificity fail to resonate when printed on sleek modern aluminum.

Specifics aside, Paletti here provides a really lovely model for critically engaging with artwork at the local level. By challenging yourself to find art that you love alongside art that you hate, and identify what about the work provokes those responses.

In order for the Louisville arts scene to thrive in the way many believe it has the potential to, it needs some dominant critical voices to speak up and drive it forward. That, really, is the purpose of criticism: to drive art forward, perpetually encouraging it to change and develop. That sort of progress is what instigated shifts from expressionism to abstract expressionism, to performance. Each iteration in that lineage acts as a critical response to its predecessor. Criticism gives art some grit, gives it an edge, gives it some tooth. And I think in this political and cultural climate, we are in desperate need of art that has the capacity to bite back.

Aaron Storm is an artist and writer living in Louisville. He is currently a BFA candidate at the Kentucky College of Art + Design at Spalding University. Initially trained as a photographer, he has developed an affinity for minimalism, as well as critical and queer theory.