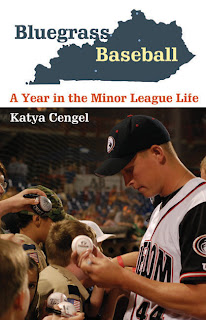

Bluegrass Baseball: A Year in the Minor League Life

by Katya Cengel

Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 272 pp., $19.95

Review by Katherine Dalton

Entire contents copyright © 2012 by Katherine Dalton. All rights reserved.

Baseball is a sport that inspires devotion. Think of the books and websites dedicated to obscure and ancient statistics. Or think of the multigenerational, pennant-less affection of the Chicago Cubs’ fans. Katya Cengel is a devotee. And it seems perfectly plausible that she, who now lives in California, would write a book about the minor leagues in Kentucky that has been printed by an academic press in Nebraska. That’s baseball all over.

Ms. Cengel spent the summer of 2010 birddogging the players, trainers, owners and staff of the Louisville Bats, the Lexington Legends, the Bowling Green Hot Rods (all minor league clubs) and the Florence Freedom (an independent league, which puts it somewhat lower on the prestige ladder). Her book is full of thumbnail sketches of people ranging from the Minnesota Twins’ Matt Maloney to the Cincinnati Reds’ Aroldis Chapman with his hundred-mile-an-hour pitch – in 2010 both men played for the Bats – to the Legends’ colorful founding president, Alan Stein. Then there are the wives and girlfriends, the host families and the fans.

There are a few statistics in this book (inevitably), but largely each of the four teams profiled here are defined by a collage of sketches meant to create a portrait in sum. We read how Alan Stein built a stadium in Lexington with no public money – a feat for which he deserves local gratitude and national respect – and how Clint Brown brought back the Florence Freedom after its previous owner cheated his creditors, bankrupted the club and landed in prison.

There’s good material on the business model of minor and independent league ball: this is summer family entertainment more than it is a sport, for the owners and the majority of ticketholders, at least. A study Alan Stein did showed that half the audience couldn’t tell you the score at the end of a game, and nearly three-quarters couldn’t identify what level of club it was – but the fans knew they had had a good time. Hence the humorous and high-energy mid-game promotions and stunts that are typical of minor league ball, such as Mr. Stein’s bets to shave his head and eat cat food, all for the sake of publicity for his club. (He had to make good on both of those. He was able to save his mustache.)

This book is also a reminder of the life the minor leagues offer ballplayers. During the season players usually live far from home and family (sometimes a continent away); they are vulnerable to trade or release on short notice; and they are vulnerable to injury and those unpredictable changes in ability that can make all the difference between a good year and a bad one. A move up or down through the system can be so dependent on luck that there’s no wonder ballplayers are proverbially superstitious. There is no job security, and at these levels – except for those high-expectations players who get a generous signing bonus – there is not a lot of money. These are young men chasing a brass ring that only a small percentage of them will catch.

“Baseball is a game of failure,” Ms. Cengel quotes player Billy Mottram as saying. For the great majority of talented college and high-school players, that is certainly true. But we are still in the stands, watching.