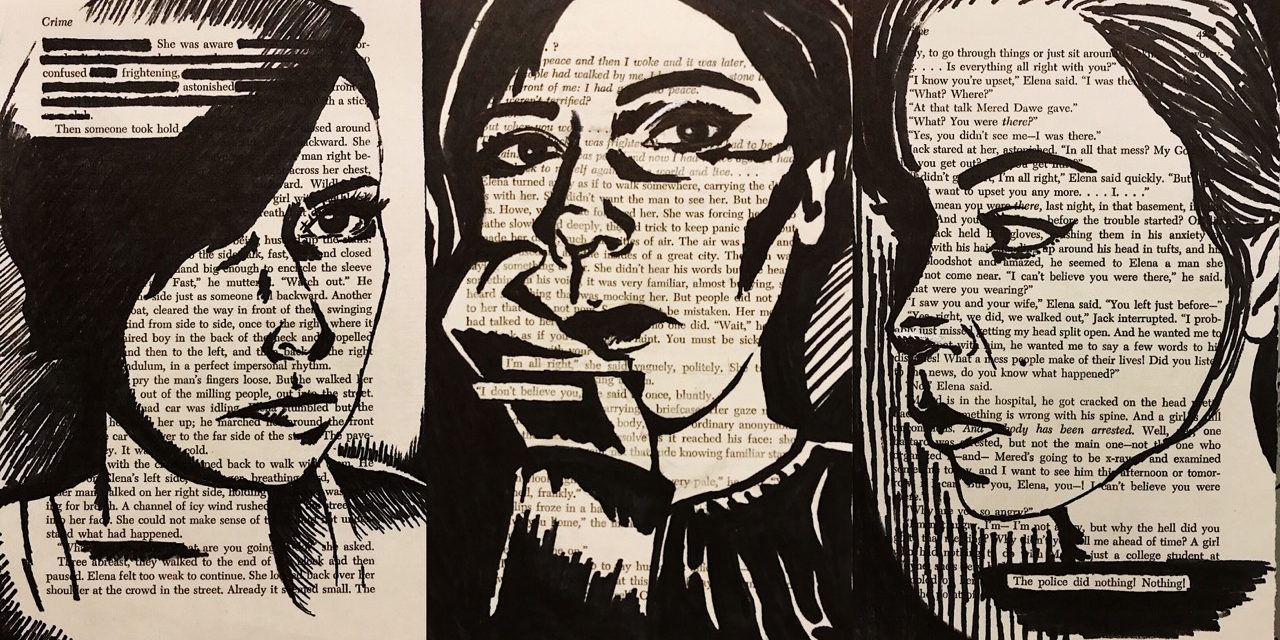

“Promotional material from “What Were You Wearing?,” artist: Alexa Helton

Editor’s note: Although this material may seem slightly off mission for Arts-Louisville, the content provides valuable context for an exhibit that has been curated by a group of students under the direction of University of Louisville Brandeis School of Law Professor JoAnne Sweeny.

By Allie Keel

Entire contents are copyright © 2018, Allie Keel. All rights reserved.

“Yeah, but what was she wearing?”

It’s a question asked in seemingly every sexual assault case, either in actual court or in the court of public opinion. The implication is generally that an outfit can have bearing on responsibility for sexual assault.

It’s a question that likely also gets asked at The University of Louisville (U of L) when they hold hearings under Title IX to address allegations of sexual assault.

This weekend, What Were You Wearing? A Survivor’s Art Installation, opening at U of L and organized by The Brandeis School of Law’s Human Rights Advocacy Program, is offering an entire collection of answers.

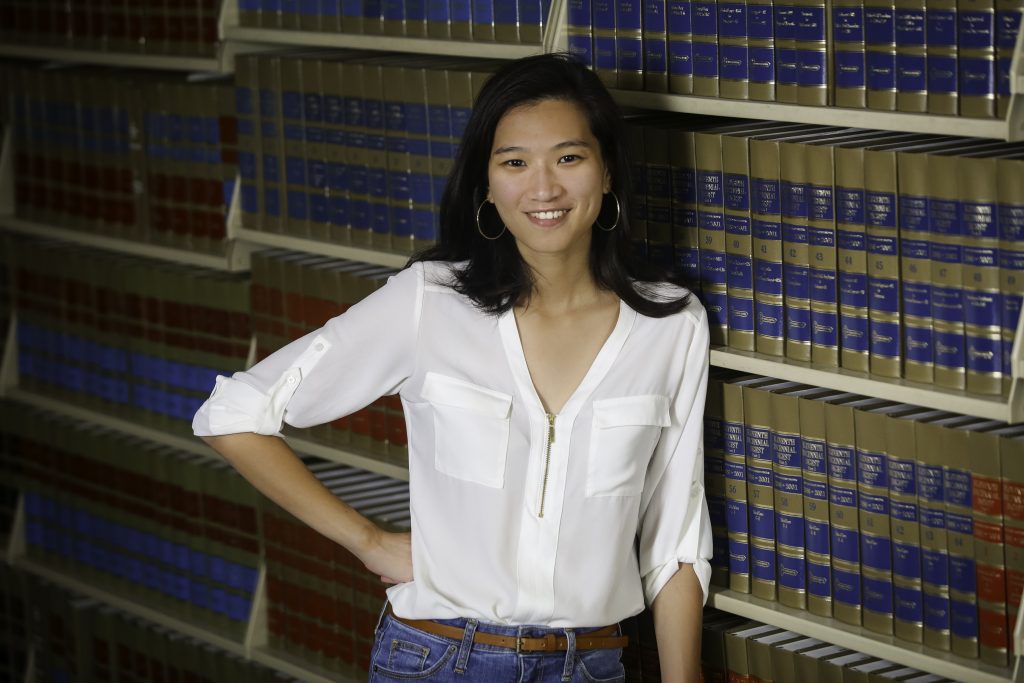

Sue Eng Ly, a law student at U of L who received The Brandeis School of Law Human Rights Fellowship, has been part of the team working on bringing the exhibition to life, spoke with me about the event, and HRAP’s mission.

“As a fellow, we have different projects. There’s one project on expungements, one projects on immigration, and then my group’s project is on Title IX,” said Ly.. “But in terms of a more substantive level, like policy and whatnot, our goal is to try and find a way to get the university to change the way it conducts Title IX hearings,” said Ly.

After being expanded by President Obama, Title IX of the Education Amendments Act of 1972 charges universities nationwide with internally handling allegations of sexual assault and sexual harassment. Universities are left to decide individually how they handle such allegations.

With the confirmation hearings of Judge Kavanaugh fresh in the public’s mind and just a day after Kentucky voters said yes to Marsy’s Law, the way society treats survivors is being examined at every level. What Were You Wearing? gets literal in the way it addresses that oft-asked question, by displaying the actual clothes that survivors were wearing on the day they were sexually assaulted.

Sue Eng Ly. Photo: courtesy Sue Eng Ly

To organize the exhibition, The HRAP partnered with The Women’s Law Caucus, who spearheaded the task of reaching out to survivors and asking if they would be interested in sharing their experiences, and their clothing.

Ly has a personal reason to want to work towards Title IX reform.

“It was something I was particularly passionate about after having gone through the process last year,” said Ly.

When she was sexually assaulted last fall, Ly decided to report the incident, and seek justice through official University channels. Her experience illuminates portions of the University’s procedure that HRAP is seeking to change.

This is the process as Ly related it. Information on U of L’s website and information that was given to the reporter by Bigelow through email corroborate Ly’s recollection.

It begins when the student making an allegation goes into the Title IX coordinator’s office.

“I described the incident, and she’s taking notes, and after that, I send them my – it’s like a statement of the incident, and they decide if they’re going to charge the person with a possible code of conduct violation.”

While the coordinator decides whether or not to investigate the student’s allegation, other steps are taken. During this period the student can decide to undergo an informal remediation.

“They also have what they call a ‘no contact’ letter, and the idea is that neither party can talk to each other in any form, at all.”

That letter is sent to both parties, ie the person making the allegations, and the person having allegations made against them.

Here is one of the first big problems Ly sees with the process, a problem exacerbated in her case by the fact that she was in class with her attacker.

“There’s no limitation on proximity. So theoretically they could sit two seats away from me.”

If the Title IX coordinator, a position currently held by Brian Bigelow, decides to pursue the allegations formally, another letter is sent, informing the students.

Next, witness statements are gathered and prepared for the hearing, where they will be read in front of a hearing panel that includes a staff member, a student, and a faculty member. That panel will also render judgment when the proceedings end.

“It’s kind of like a trial, but each side has an advisor. That advisor can like whisper things to them in between questions, but only the parties are allowed to ask questions,” said Ly.

“Only the parties,” meaning that when it was time for someone to ask Ly’s alleged rapist questions about what he did to Ly, the questions had to come from her. There are no representatives to do the talking for complainants, although they are allowed to bring someone to advise them.

Ly likewise had to be ready to answer questions put to her by the accused.

It’s worth noting that there is a measure in place to keep the complainant and the accused from directly addressing each other.

Title IX coordinator Brian Bigelow offered the following clarification:

“The accused student and the complainant do not have the right to directly question each other unless both parties agree. If both parties do not agree to directly question each other, all questions from the accused student to the complainant and vice versa will go through the hearing official.”

Ly’s alleged rapist chose not to question her, but given statistics that suggest that only 6% of rape accusations are false, U of L’s policy creates the likelihood that a sexual assault survivor will be grilled by their rapist while a panel from the University either watches or helps.

In Ly’s hearing, that panel was made of two men and one woman.

The specifics of the rest of Ly’s hearing contain a lot more head-scratching moments, including at one point hypothetical questions being put to an absent witness.

When a decision was rendered, the hearing found that there had been no breach of the student code of conduct. Ly said the experience left her feeling abandoned by the institution, and dehumanized.

‘I was like, there has to be a better way” said Ly.

It’s easy to see why the Human Rights Advocacy program is trying to change those proceedings, and find a process that safeguards the rights and safety of both the accuser and the accused.

During Ly’s hearing, she wasn’t ever actually asked what she was wearing, though there were many aspersions cast that Ly found deeply upsetting.

Regardless, when The Human Rights Advocacy Program and the Women’s Law Caucus was seeking clothing from survivors, Ly was quick to add her own clothing to the exhibition.

“I donated my clothes because doing so reminded me that I have nothing to be ashamed of,” said Ly.

What Were You Wearing? A Survivor’s Art Installation opens this Saturday, November 10th at 5 pm, at the Cardinal Lounge in The University of Louisville’s Student Activities Center, 2100 South Floyd Street.

There will be a reception at 5:30 pm in the Mosaic Room in the Brandeis School of Law Library, with guest speaker Gretchen Hunt, from the Attorney General’s Office of Victim Advocacy.

Allie Keelis a Louisville based playwright, poet, storyteller, and freelance journalist. They have been published in Word Hotel, their plays have been produced by Theatre [502] and Derby City Playwrights, and they were invited to read their work at the 2014 Writer’s Block. They are frequent contributor to LEO Weekly and Insider Louisville, where they have been given the (informal) title of “Chief of the Bureau of Quirk.”