Interview by Katherine Dalton

Entire contents are copyright © 2020 by Katherine Dalton. All rights reserved.

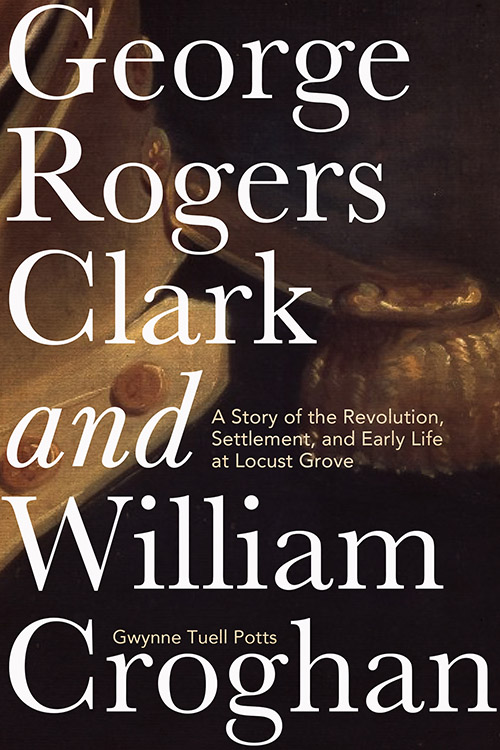

Gwynne Tuell Potts is a historian, Louisville native, and the former executive director at Locust Grove, the final home of Louisville founder and Revolutionary War hero George Rogers Clark. Her new book, George Rogers Clark and William Croghan: A Story of the Revolution, Settlement, and Early Life at Locust Grove has recently been published by the University Press of Kentucky.

Potts is also the author, with the late Samuel W. Thomas, of an earlier book on Locust Grove and Clark. Katherine Dalton interviewed her about Clark’s life, the Croghan family, and her favorite books on the history of the Ohio River Valley and Federal period.

This is the first of three parts.

Q: What does every Kentuckian need to know about George Rogers Clark?

Potts: Several things. First of all, no matter what we learned in school, it was George Rogers Clark, not Daniel Boone, who became the military and civic commander of the American West, when he was just 25. It was he who was elected by the people of Harrodsburg to represent them in Williamsburg. And it was he, in the early 1780s, who was considered the odds-on favorite to become the Kentucky territorial governor, when such a thing came to pass.

Boone was a trapper. He was a settler. He was an explorer. He was a wild and crazy fellow. But George Rogers Clark was Kentucky’s first leader, and many people don’t realize that.

I’ve also heard people talk about Clark in two ways: one, that he was well-educated, and secondly, that he was illiterate. Neither is true. He was mildly educated, but for the year he endured a formal education, he was classically trained. And when you look at his writing, beginning with probably the November 1779 letter to George Mason, some of it is obviously scripted with an audience in mind. I’ve been struck by the similarities in structure and perspective and even some of the subject matter between these public writings and the style used by Tennyson in creating Ulysses. But Tennyson didn’t publish that poem until 25 years after Clark’s death. Clark’s reference wasn’t Tennyson; it was Homer. So while he had a short education, he had a lasting education.

He was an information sponge; he found information wherever he went. His intellectual passions were science and ancient history. He was an accidental soldier who looked to the Enlightenment and Thomas Jefferson to create his personal philosophy–and if we don’t go any further than that, we can see why he was pretty much alone on the frontier.

But Clark lived in New York City for three months in 1784. He was in Philadelphia, the nation’s capital, when he was held for questioning in 1798. He wasn’t such a rustic that he couldn’t find his way to the northeast and work and live in those cities. He was just a deeply complicated person, and I’m not sure he was ever comfortable in his own skin.

Q: I’ve heard you say the world of Revolutionary-era America was very small—that everyone knew everyone else. How do the lives of Clark and his brother-in-law William Croghan reflect that observation?

Potts: Let’s look at William Croghan, since we’ve been talking about Clark. He was Lucy Clark’s husband and George Rogers’ brother-in-law, and he was introduced to America through his uncle, George Croghan, who was Sir William Johnson’s deputy Indian supervisor. And by way of his uncle he met not only Johnson but Ben Franklin and Ben’s son William, who was the colonial governor of New Jersey. He met Philadelphia merchants Barnard and Michael Gratz, Mohawk Chief Joseph Brant, and George Croghan’s second daughter Katherine, who was Brant’s future wife. William also met George Croghan’s older daughter, Susanna, who married a British officer whose uncle was Colonel Mark Prevost, the first husband of Aaron Burr’s future wife. Croghan knew Burr already, from the Revolution. They were both in the New York-New Jersey campaign; they were at Valley Forge together, and the Battle of Monmouth; he also knew Baron von Steuben, Alexander Hamilton, Henry Knox, the Marquis de Lafayette, and for four years he rode with George Washington in the Continental Army. He was regularly sent into Philadelphia from Washington’s various New Jersey camps to carry and receive information to and from the Continental Congress. He was well-connected.

Clark, on the other hand, was born on a farm–but it was adjacent to Thomas Jefferson’s father’s plantation, Shadwell. While the fathers obviously knew another, Jefferson and Clark’s relationship really didn’t materialize until those men were adults, I would guess beginning with Clark’s 1777 trip to Williamsburg to plead for Virginia’s protection for its Kentucky settlers. From that point forward Jefferson always would be Clark’s most important connection. But he knew nearly everyone who mattered west of the Appalachians: Daniel Boone, Isaac Shelby, both of the Todd brothers, Richard Butler. He also knew von Steuben, John Neville, Lord Dunmore. Patrick Henry was his father’s lawyer.

He knew and enjoyed reciprocally respectful relationships with Cayuga chief Logan, with the Piankeshaw chief Tobacco and his son, Shawnee chief Moluntha and his wife, and Miami chief Little Turtle. In fact, after the frontier war paused in 1795, Little Turtle’s daughter married William Wells, who was the brother of Kentucky militia leader Sam Wells, who lived next door to Clark’s brother-in-law Richard Clough Anderson. Sam Wells lived on what is today the Hurstbourne Country Club golf course; Anderson lived on Shelbyville Road at today’s Hurstbourne Lane. Little Turtle came to Louisville frequently to see his daughter, and on at least one occasion he walked over to Anderson’s house to meet his personal hero: George Rogers Clark.

There were few doors in Revolutionary or Early Federal America that William Croghan and George Rogers Clark together could not open.

Q: Clark was a very young hero. What achievement or quality of his do you find most remarkable?

Potts: With the exception of Simon Kenton, Clark was younger than any of the frontiersmen he deputized as his officers, and while he did arrive in Kentucky with some middling social credentials, he didn’t come from a powerful Virginia plantation connection. His forebears were not noted military men; in fact, his mother’s family were inclined to the ministry and the schoolhouse. Clark was simply that rare thing: a natural leader of men. He was direct; he was honest; he was brave; he was intelligent. Jefferson took the time during his term as Washington’s Secretary of State to write to Henry Ennis about Clark, and he said, “I know the greatness of his mind, and no man alive rated him higher than I did.” Clark was a unique figure on the American frontier.

Katherine Dalton (Boyer) is a writer and editor, and a former board president at Locust Grove. She is a contributor to Wendell Berry: Life and Work (University Press of Kentucky), Morris Grubb’s volume Conservations with Wendell Berry, and Localism in a Mass Age: A Front Porch Republic Manifesto.