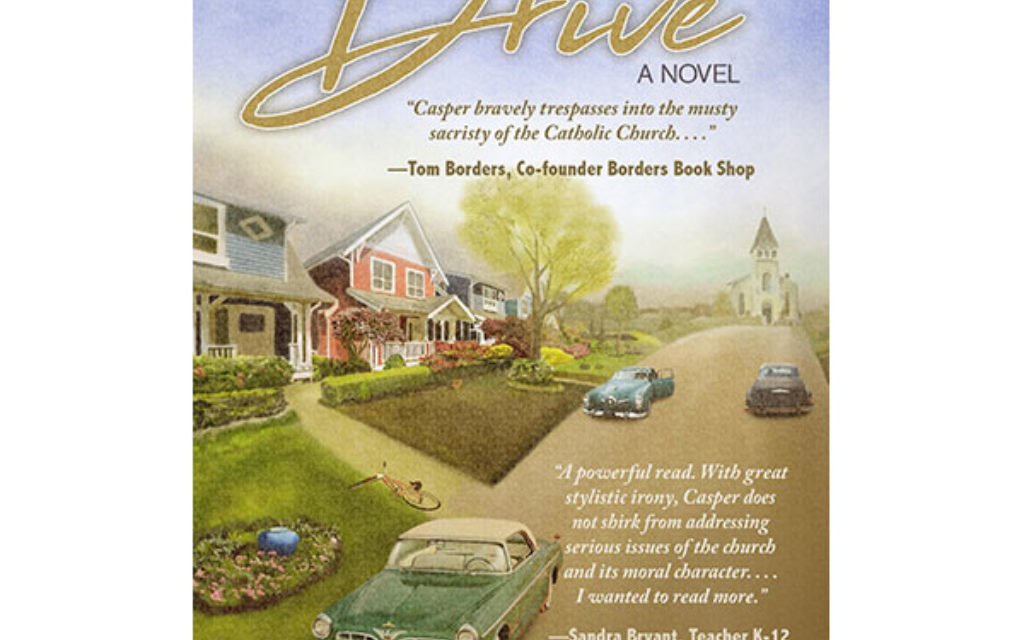

Sycamore Drive, A Novel

By Charles Michael Casper

Old Stone Press

Paperback, 185 pages, $14.95

A review by Keith Waits

Entire contents are copyright © 2020 by Keith Waits. All rights reserved.

The shelf life of social scandal may vary depending on the scope of the scandal, but it cannot help but seem as if we are more easily prone to forget even the most outrageous events as we move forward in time. Now is the time of a global pandemic fighting for attention with a rising tide of social protest led by Black Lives Matter about police brutality, both of which threaten the very fabric of American communities, but only a few years ago the Catholic Church in the United States was rocked by the revelations that thousands of priests had been pedophiles preying on children.

Of course, you remember the headlines in print and the incredulous broadcast media reporting on the subject, but can you pin down the point at which all of it was resolved? Like the racial injustice driving today’s protests, sexual abuse by Catholic priests is a social disturbance that dates back too many generations in our history. In his novel, Sycamore Drive, Louisville-born Charles Michael Casper reaches back to the 1950s to examine how such the problem impacts the small Illinois town of Riverport.

An offbeat set of characters come together uncovering, investigating, and eventually taking action against Monsignor Donnely, the high-ranking priest in charge of St. Mary’s Catholic Church. Father Stephen Watson, a young, charismatic man newly assigned to St. Mary’s, Norman Hudson, an isolated man who is to all appearances autistic years before that diagnosis would come into being, and Sister Alissa, who teaches at a Catholic school in a neighboring community, all play a key role in the final passages of the drama that unfolds.

It goes without saying that any scandal is contained because what Casper illustrates here is one story that we now know was being repeated over and over again in parishes all across the country; personal narratives of trauma and cover-up that would only truly come to light more than 40 years later. The years-long extensive coverup involved offending priests being reassigned after a healing retreat only to quite often begin once again preying on children in their new parish. Casting this scandal in such an intimate scale makes for a manageable, insightful work of fiction for a first-time novelist.

Yet, that is also the frustration here. I admire the approach and structure of Sycamore Drive, but Casper is a good enough writer to make me wish he had pushed himself to develop the narrative more, flesh out the characters beyond their functionality, and let the story breathe a bit more. He does it in the early chapters, but as the plot gathers steam, the events are documented while the resonance of the characters’ involvement gets short-changed. Don’t get me wrong, I value economy in writing, but it is a good quality in thrillers and crime fiction, whereas this tale cries out for more of the nuance that lives between exposition.

Still, Casper’s book has good bones and there is as an eye for subtle detail in his prose. Those good qualities are most assuredly found in Norman Hudson. He is introduced in the first sentences, and for a time his presence suggests that Casper has a different theme in mind than questioning the institutional religious stranglehold on morality. Why is Norman here? I think it is to immediately force the reader to question stereotypes. Norman has proved problematic for his family and community, once having his inevitably unfettered curiosity mistaken for voyeurism, but before the last page, we have found evidence that Norman’s moral and ethical foundation is more sound than many of the other people we find in Riverport.

It is arguably the most original and impactful feature of the story, that Norman stands for the clear delineation of right and wrong that we now know was missing in how the American Catholic Church systematically mismanaged a deeply disturbing crisis, fundamentally misunderstanding the problem, and covering it up with money and patronage while thousands of victims suffered because the very institution that was charged with emotional and spiritual comfort was the source of the trauma. Sycamore Drive takes the sensational headlines that rapidly began to fade from memory and put them in a very personal context.

Yet, I could not help but ponder the question of whether or not the victimization of children by Catholic priests has ended. That Casper has set his story in the mid-Twentieth Century underscores the pernicious durability of such things, and whether the Catholic Church will ever be capable of ridding itself of the problem once and for all.

Keith Waits is a native of Louisville who works at Louisville Visual Art during the days, including being the host of LVA’s Artebella On The Radio on WXOX 97.1 FM / ARTxFM.com, but spends most of his evenings indulging his taste for theatre, music and visual arts. His work has appeared in LEO Weekly, Pure Uncut Candy, TheatreLouisville, and Louisville Mojo. He is now Managing Editor for Arts-Louisville.com.