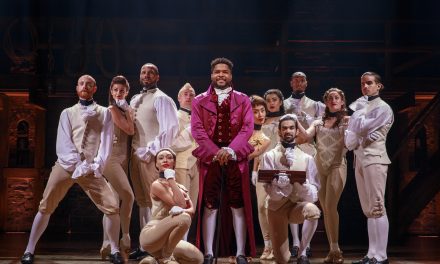

Tom Luce & Jason Maina

Imagining Heschel

Selections From A Play

Written by Colin Greer

Directed and with adaptations by David Y. Chack

A review by Keith Waits

Entire contents are copyright © 2020 by Keith Waits. All rights reserved.

We believed that we had come so far, yet the voices for social change from more than 50 years ago often sound as if they are talking about 2020. One such voice was Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel.

Heschel was a Polish-born theologian who survived the holocaust, and after moving to America, worked with Martin Luther King, Jr., advised Pope John XXIII, and was deeply involved in protesting against the Vietnam War and for civil rights. He was a philosopher shaped by the tumult and tragedy of the mid-Twentieth Century.

Colin Greer’s text imagines a handful of key encounters between Heschel and contrasting individuals both ordinary and high placed. There are two long exchanges with U.S. Cardinal Bea (Richard Kartz), one pleading with Heschel to come to Rome to help counsel the still-developing Vatican II, and another at a Kosher restaurant once he gets there, that frame a more academic, albeit collegial debate on the relationship between Christians and Jews. The history is fraught with anti-semitism and the moment is ripe with opportunity to move past the hateful divisions of the past.

Heschel has a much more personal relationship with Jonah (Jason Maina), the young Black man who has taken over from his father the job of being the Rabbi’s driver. Jonah is filled with rage at what is happening to African Americans in the streets yet also enlists to serve in Vietnam, positions that seem contradictory and confusing to Heschel the warrior for Peace. Maina’s hair doesn’t match the period, but his impassioned read of the character seems to intentionally connect to protests in the streets of 2020.

Bailey Storey plays Father O’Malley, a young Vatican priest who gives explicit voice to the anti-semitic claims present in Irish Catholicism, defending that heritage in ways that echo the sentiments of Americans holding onto the “Lost Cause” culture of the South, and Lindsey Palgy is television host Carol Radnor, who gives the Rabbi a potent dose of 1960’s feminism and sociological argument.

All of which neatly ticks off a number of boxes, but Greer avoids being overly tidy because this was a time of struggle for representation, however problematic the individual choices may be. It is also important to recognize that Heschel doesn’t win every argument; he is no theological superhero. His weapons are wit, intellect, and wisdom won during the most difficult of times, but he is also beaten down by grief and suffering, even though he strives to remain hopeful.

As Rabbi Heschel, Tom Luce captures all of that in the sunken eyes that seem pulled down by his profound gray beard. He shows how this man has carried not only his own burdens but the weight of so many others. He grieves for the death by assassination of his good friend Martin, and he grieves for the misbegotten anger and bitterness felt by those around him. The temptation to step into caricature with the character might defeat a lesser actor, but Luce walks the line with discipline and attention to detail that points to everything Heschel must be outside of these selected vignettes. Even though we spend an hour with him, the traces of the larger life are present in this performance.

Richard Kartz is the very model of the prelate executive, displaying a fine balance of clerical ascetic and avuncular charm. Jason Maina seems impossibly young but appropriately so, as he stands for a generation decimated by war both abroad and at home. Bailey Storey’s equally youthful priest is not as fleshed out, but the restraint he brings to his Irish dialect is indicative of his work here. Lindsey Palgy looks and sounds like she walked out of an episode of Mad Men, but makes her briefest of exchanges with Heshel leave a distinct impression.

Out of the taped or filmed theatre projects that have been delivered recently, the unfussy professionalism of the simple, three-camera approach is handled with skill, but I was most grateful that David Y. Chack and Videobred director Raphael Cecil were not afraid to get the camera up and fill the frame with some vivid expressionistic visuals during what is the emotional climax of the piece. If the tactic of most filmed productions is to make us feel as if we are in a theatre, taking even this small advantage of the digital medium is crucial in lifting us out of those imagined seats for a moment. It effectively substitutes for the immediacy of being in the same room, wherein we expect that effect to come solely from the live performance.

To say that ShPlel and Bunbury have in Imagining Heschel found material that speaks to our moment should feel unnecessary; what else should theatre be doing? Yet such choices have felt more self-conscious in the last few years, overt attempts to stop the bleeding in a society that struggles to cope with being turned inside out. We hear hope in the words of Rabbi Heschel, hope that such hearts and minds as his might still emerge now to help us through a dark time, because without them we might only despair.

Imagining Heschel

Available On Demand December 1-20, 2020

ShPlel Performing Identity &

Bunbury Theatre

Tickets: $15 GA or $10 students

$12 for groups of 10 or more

Keith Waits is a native of Louisville who works at Louisville Visual Art during the days, including being the host of LVA’s Artebella On The Radio on WXOX 97.1 FM / ARTxFM.com, but spends most of his evenings indulging his taste for theatre, music and visual arts. His work has appeared in LEO Weekly, Pure Uncut Candy, TheatreLouisville, and Louisville Mojo. He is now Managing Editor for Arts-Louisville.com.