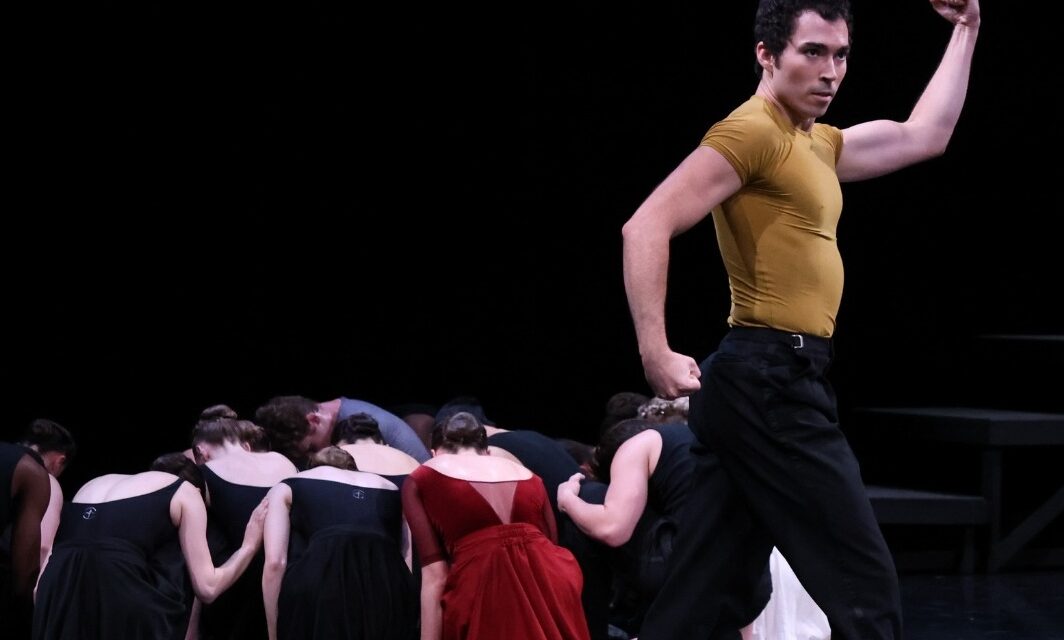

Danny Scofield in Cold Virtues. Photo: Kateryna Sellers

Distilled

Various choreographers

A review by Amberly M. Simpson

Entire contents are copyright © 2023 by Amberly M. Simpson. All rights reserved.

The Louisville Ballet kicked off their Season of the Commonwealth with Distilled, a three-part production featuring performances from some of their favorite repertoire over the years. While this production was originally scheduled to be performed at the Brown Theatre, it transitioned to an in-house performance, inviting audiences to experience ballet and contemporary works in a much more intimate setting that not only allowed for a more personal experience but a more visceral one as well!

—

The show opened with Appalachian Spring by Andrea Schermoly, set to the same music as was composed for Martha Graham’s 1958 work by the same title. In Schermoly’s own words “Graham’s version was inspired by the lives of the Shaker community; in my version, I pay homage to both the style and inspiration, but lean less specific in the community origins. “

Much like Graham‘s version of Appalachian Spring, the narrative itself tends to wander, at times feeling redundant. However, I found that Schermoly‘s movement, as a contemporary work not bound by a specific technique, was much more striking and interesting than the original. I particularly enjoyed the strong visuals this piece formed using the platform set pieces to frame the space and interactions.

The costumes were simple, with each of the four characters in different colors, and the ensemble in all black. I enjoyed the simplicity of the costumes for their ability to really center the piece in the movement and narrative, however, the black of the ensemble read more funeral than a wedding, especially when paired with the more dramatic movements of the music and a lack of consistency in expression from the ensemble dancers.

Despite portraying a wedding, the couple-to-be never seemed to make eye contact with each other while they were dancing together, except for two to three explicitly choreographed moments. Schermoly’s Choreographer Notes state that “[the couple is] in love and full of optimism — however, they grapple with the trials and tribulations that will inevitably befall them as a couple and in life.” It would have been nice to get a little bit more of the love and optimism side of things, to see more of the tenderness of their relationship alongside the tension and disconnect. That said, when those moments did occur, they were incredibly satisfying!

David Senti did a particularly striking job in his role as the Counselor, showing off the versatility of his movement ability. I will say, I might have considered switching the casting on the two male leads. While both of them are clearly proficient and versatile performers, I found that Senti’s combined movement and expression read more youthful, sweet, and innocent in the intimate performance venue, whereas Mark Krieger’s (who played the Husband) movement read more mature and powerful, but also cold and removed. Aesthetically, these qualities seemed to lend more to each other’s characters, and I kept thinking how much both of these dancers would have done a fantastic job in each other’s roles.

—

The second work in the show was Adam Hougland’s Cold Virtues, inspired by Les Liaisons Dangereuses/Dangerous Liaisons. This work was a restaging of the very first work that Hoagland set on the Louisville Ballet 20 years ago, making for a nice tie-in to their Season of the Commonwealth, Made for Kentucky, by Kentucky.

Of all three works in the show, this one definitely had the strongest composition, not only due to the construction of the choreography itself, but the clarity of characters, and their intentions and outcomes. The movement vocabulary was cohesive and rooted in several recurring motifs that were continually modified in their use and evolved throughout the piece.

Though none of the costumes for this piece were the same, they felt as cohesive and aligned as the movement vocabulary, with everyone wearing different shades of red, brown, gray, and beige. Even without separating out the characters distinctly in their costuming, the choreography itself made it clear who each character was, and their relationship to each other.

Additionally, this work more intentionally felt like it was designed for the intimate setting it was featured in for Distilled, with the “evil” lead characters (played by Ashley Thursby and Daniel Scofield) making more direct eye contact with the audience repeatedly throughout the production, as if we too were in on their schemes.

All in all, this work was engaging the whole way through, and you did not need to be familiar with the plot of Les Liaisons Dangereuses/Dangerous Liaisons to be able to follow the story that was unfolding in front of you. Bonus points for accessibility!

—

The show concluded with Act III of Raymonda, a classical ballet work by Marius Petipa. This piece had all the usual tropes and structures of a classical ballet piece. Perform, pose, applause, perform, pose, applause, eat, sleep, rinse, repeat. It’s a structure that is, from a story craft perspective, outdated, so I wouldn’t recommend viewing this work through the lens of narrative. However, if you are looking for a stunning representation of classical ballet movement and structures, this is certainly one of the finest examples out there and the Louisville Ballet does it full justice!

The intimate setting made viewing this work a very interesting experience. Of the three works in the show, this one was most explicitly designed for a traditional large house proscenium space and it did not appear that any adaptations were made specifically for the change in setting. While the close proximity removes the sense of glimpsing into another world, you don’t exactly feel a part of it either. Even if you’ve seen ballet before, perhaps even this specific ballet, it felt like an entirely new experience to witness a classical work so up close and personal!

Of the various solos, duos, and small group numbers featured throughout the piece, two in particular stood out to me. The first was soloist Brienne Wiltsie. While her execution of the movement was masterful, I just couldn’t help but feel delighted by her performance. Her face very genuinely reflected the playful quality of the movement and music, making her feel distinctly more present and more connected with the audience. I found myself actually smiling as I watched her!

The second soloist who stood out to me was Aleksandr Schroeder. Like Brienne, he brought a distinct authenticity to the movement with his expression, but where Brienne was more playful, Aleksandr was more light and whimsical. The solo he performed was absolutely brutal, requiring a great deal of skill; you could hear him breathing, making the execution and the fact that he maintained his lightness the whole way through all the more impressive.

I want to acknowledge that, as a restaging of a classical work, the ballet is bound by rules in terms of how these works are represented. However, as a society, we have also generally acknowledged that dressing up as other cultures as a costume is considered inappropriate and perhaps even offensive. I have to wonder where this line falls with classical ballet works, where other cultures, and the dances of other cultures, are regularly appropriated and featured. In the case of Raymonda, the ballet opens with an appropriation of “Hungarian” dance in mock Hungarian traditional attire. Is there a way of honoring these classical works while also being responsible to present-day ethics? If not, perhaps it is best that we make different choices of what work (or what parts of those works) we choose to honor.

—

As a whole, it felt like many of the performers struggled with the shift to a small, intimate venue setting. Performatively, most of the works featured in this show were very clearly designed for distance viewing. I, personally, absolutely adore intimate performance spaces and appreciate performances done in this way far more than the removed nature of a large proscenium, however, it certainly requires a shift on the part of the performers and creators alike. While some performers really came alive in this, I found that others really struggled. There were lots of darting eyes and lots of challenges to maintain faces throughout. However, I do also want to acknowledge that this struggle was not wholly the weight and responsibility of the performers. Part of the reason Adam Hougland’s work read as distinctly stronger was because, with its composition, it mutually set the performers up for success. It was difficult to pick out any one person who shined in Cold Virtues because they pulled off something much more difficult: they shined as an entire collective. So when I say that the move to an intimate performance venue requires a shift from both performers and creators alike, Adam Hoagland understood the assignment and delivered it. As a result, his dancers were able to better support and perform the work without the awkwardness of “I need to put on a face for this piece that was meant to be viewed at 50+ feet away”. All of this to say, I’d love to see the Louisville Ballet more deliberately lean into this opportunity to produce ballet as a more visceral and intimate experience for their audiences!

In terms of thematic elements, I was hoping that this show might produce a stronger connection to their idea of a Season of the Commonwealth. There wasn’t anything particularly *Kentucky* about the production. Indeed, I saw more of Europe than I did of Kentucky, despite the tagline “Made for Kentucky, by Kentucky”. While, as previously mentioned, Hoagland’s work had some subtle tie-ins, Schermoly’s piece removed the elements that tied the piece more explicitly to this region of the country, and Raymonda’s only tie-in was that the ballet likes the piece. It would be wonderful to see the experiences and lives of the people of Kentucky adapted into these stories more explicitly. Perhaps the shows could feature more native choreographers as well! There is so much room to play with what the “Season of the Commonwealth” component means to each production. I hope that future productions this season will lean into this as well!

As we (hopefully) know, The Louisville Ballet is one of the oldest and largest ballet companies in the country. The quality of their work is unquestionable; they know how to deliver high-quality dance to their audiences! Distilled did not disappoint in this regard and made for a fantastic kickoff to what is bound to be an equally exciting season.

Distilled

October 13 – 15, 2023

Louisville Ballet

315 East Main Street

Louisville, Kentucky 40202

Louisvilleballet.org

Amberly M. Simpson is a Choreographer, Dancer, and Dance Educator/Advocate originally from Glendale, California. She specializes in Modern, Post-Modern, and Contemporary Dance forms, creating work that is often interdisciplinary in nature to provide commentary on social issues and the human condition. By day, she is the Dance Director and Musical Theatre Co-Director at Noe Middle School, but by night she serves as the Artistic Director of Ambo Dance Theatre. Amberly’s work has been presented at venues such as the American Dance Festival Movies by Movers, the Going Dutch Festival, the Midwest Regional Alternative Dance Festival, and Princeton Research Day where her collaboration with Dr. David Vartanyan received the Impact Award. In 2019, she was honored as one of the Hadley Creatives through the Community Foundation of Louisville, and in 2022 she worked alongside her Dance colleagues in the Jefferson County Public Schools to launch the first ever All County Dance program for the state of Kentucky.