Krapp’s Last Tape directed by Alec Volz

Happy Days directed by Michael Harris

It’s part of the legend of Waiting for Godot that an early review of the play summarized it thusly: “Nothing happens, twice.” While it might sound snide, this comment came from one of the foremost scholars of Beckett’s work during the writer’s life.

So while it may sound like a swipe, take it as obeisance to the bravery and audacity of producing two of Beckett’s plays in the same evening when I report that, in this inaugural production of Michael Harris’s new Masterworks Theater company done in conjunction with our resident classical theater group, nothing happens three times.

|

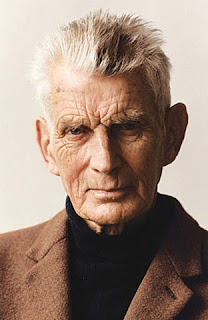

| Samuel Beckett |

A novelist and playwright, Beckett’s theatrical legacy is of being perhaps the most anti-dramatic dramatist of all time. Over the course of his career, he sought to demolish most every convention of the stage. His characters wander about aimlessly, speaking half-finished thoughts, engulfed in lives of misery occasionally illuminated by memories (delusions?) of better days past. He went so far in his deconstruction of theater that one of his plays is nothing more than a woman’s mouth in spotlight. Early productions of his work inspired everything from near-riots to walkouts. He was no friend to the audience.

To an actor of sufficient skill and fortitude, however, he can be Santa Claus. It’s appropriate that Barrett Cooper and Alec Volz, the actor/director team responsible for Krapp’s Last Tape, are members of the educational team at Walden Theatre. One can imagine their students receive a fairly substantive immersion in Beckett, as they deliver a seminal performance of one of Beckett’s most famous works (behind Godot, and perhaps Endgame).

Briefly, Krapp’s plot is the titular character, at age 69, listening to tapes made on birthdays decades before, reflecting on recent events in his life and their rapturous and deleterious effects. In one act, Beckett runs the gamut of human experience with a simple premise and the power of suggestion through words, actions and the lack thereof.

The key to playing Beckett is that everything, every single thing, the actor does is important. It is so because he is called on to make so much seem like so little. As Krapp, every twitch Cooper makes is loaded with meaning. He is the prototypical Beckett man through and through: hobbling, wheezing, profane, impish, reflective, pained, sad, defiant, defeated…he is everything a man can be, and the wear and tear is all there on the stage. Volz and Cooper play the wonderful comedic ironies for all they’re worth: Krapp holds scraps of writing and keys an inch from his eye to register them, then unnervingly eyes an audience member as he demonstrates the more obscene qualities of a banana. Krapp may be one of the most difficult roles I have seen performed, as so much of it is rendered in helpless pauses and misdirected business. Cooper leaves the audience completely affected as the lights go down on him, his recorded declarations juxtaposed against all we have seen of this poor soul. Breathtaking work.

The two-act Happy Days is the more difficult piece for a variety of reasons. Michael Harris’s director’s note explains that Beckett sought to dramatize the life of a woman as he saw it. Thus we have Winnie, trapped beneath a mercilessly pounding light, kept awake by the unyielding ring of a bell, with only her spare collection of personal effects to sustain her existence and a barely-present husband with which to share the collapsing house of cards that are her thoughts. She is buried up to her waste in act one, to her neck in act two. And as all women are expected to do under impossible circumstances, she is to remain a lady. Trapped as she is, she attempts to find joy in memories, playing with her properties, and idle talk. It is a desperate struggle.

Whether intentionally or not, pairing these pieces gives a stark insight into the difference between men and women as Beckett sees it. Brevity and gender serve Krapp well. Beckett made his point in one act. Krapp is a man. To deal, he does. As Winnie, Laurene Scalf cannot move. So to deal, she talks. She thinks aloud, her thoughts ricocheting around in the manner that may have indirectly influenced Durang’s Bette. While Cooper plays Krapp’s every flinch with a focus and decisiveness, Scalf glides through Winnie’s struggle. Her affectations are more muted and tentative: eyes downcast, somewhat monotone and over-pronounced in delivery. Watching her becomes tedious, but then, this is Beckett. That may just be the point. It is when Scalf pulls inward that her emotions become a desperate hiss, like a gas leak in search of a flame.

More than a few people have called Winnie “an actress’s Hamlet.” The role is one in which to show one’s skill. I would suggest the role is even more of an endeavor than The Dane. Winnie is a thankless role, almost designed to lose the audience, and Scalf plays her with conviction to the final blackout. Michael Harris plays Willie, Winnie’s husband, with the sluggishness and pained exasperation Beckett demands. Though the audience grew restless, Willie’s final action drew the welcome release of laughter at precisely the right moment. As exasperating as Happy Days is, it may be indicative that Beckett knew exactly what he was doing.

It’s difficult to say a Beckett double bill is an evening to be enjoyed. More to the point, it is to be appreciated. Savage Rose and Masterworks are to be commended, if for nothing else than gamely staging material few would dare to touch with so much theater to choose from in Louisville. Perhaps the best ending would be to leave the lights down after curtain call. I suspect few will see these plays, but on those that do, they will leave their mark.

Krapp’s Last Tape & Happy Days

August 29, September 1-3 at 7:30 p.m.

September 3 at 2:00 p.m.

Nancy Niles Sexton Stage at Walden Theatre

1123 Payne Street

589-0004

www.savagerosetheatre.com

Entire contents copyright 2011 Todd Zeigler. All rights reserved.