|

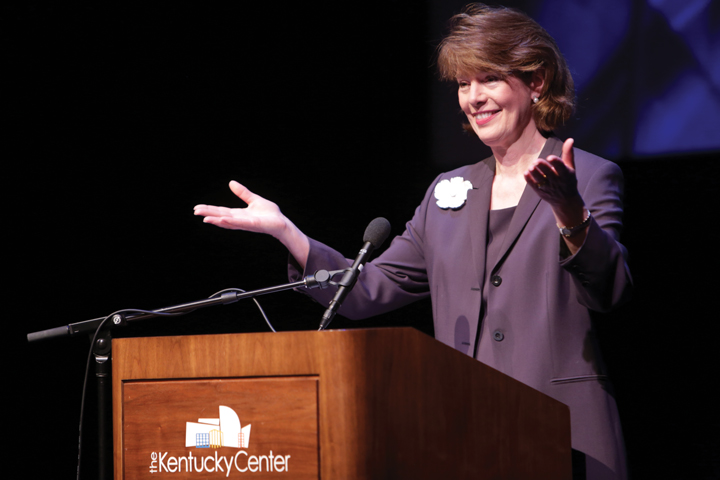

| L to R – Dale Strange, Matt Orme, Barrett Cooper, Carol Willimas & Julane Havens in Buried Child. Photo courtesy of Bunbury Theatre. |

Buried Child

Written by Sam Shepard

Directed by Steve Woodring

Reviewed by Keith Waits

Entire contents copyright © 2012 Keith Waits. All rights reserved.

How is it that Louisville has never seen a production of Buried Child? The play won the Pulitzer Prize in 1979 and elevated Sam Shepard to THE important American playwright of his time, yet it has taken more than 30 years to come to a Louisville stage. We can be grateful to Bunbury Theatre for finally rectifying the situation, proving again why local theatres such as this matter. This powerful presentation is a lesson in both contemporary theatre history and a testament to the strength of the local talent pool.

Shepard examines the dark underbelly of the American experience and the dissolution of the American dream by showing in morbid and unrelenting fashion a set of archetypal characters who are so profoundly damaged as to be unrecognizable. They were a farming family, father and sons born to work the land, and a stalwart mother, all expecting to reap the harvest. Norman Rockwell is mentioned at one point; one might also bear in mind Grant Wood’s famous painting “American Gothic” in contemplating the upright standard bearers of the heartland that this family was meant to be.

But the family unit has been devastated by sin and disappointment so deep that it will never recover and a secret so toxic that its denial has corrupted them all to the point of ruination. The crops have been abandoned for years; the father is a bitter, depressed alcoholic; the two sons are emotionally or physically crippled; the mother is lost in an illusion of normality that depends on the kindness of a “boyfriend” who is a singularly ineffectual clergyman.

In Act Two a grandson arrives, with girlfriend in tow, both of whom provide the audience entry into the characters’ lives; surrogates, if you will, to ask the questions that have risen in our minds during the cryptic and mysterious first act. By the end, how each of these young people react to the circumstance will frame our understanding of what Shepard is trying to say here. It is important to realize that Buried Child originated before the casual discussion of “dysfunctional families” became ubiquitous. In a society where a good majority now identifies themselves as the result of such troubled family structures (Americans never want to be left out), Shepard’s play may seem to be revisiting well-trod groundn But the truth, never more elusive than in this story, is that Buried Child is a seminal work that has proven to be a great influence on so many who came after. This is one of the foundations of that trend, and I would be hard-pressed to name a better example from the 30 years since its debut.

Director Steve Woodring has chosen his cast with care, and they truly deliver. Dale Strange has a small role as Father Dewis, but he perfectly captures the befuddled ineptitude of a priest who is in over his head and compromised by his own questionable behavior. Ty Leitner looks like Glen Campbell circa 1970 as the grandson, Vince, and while the image serves to nicely establish a place in time, the actor also handles the shift in temperament between his two scenes with energy and confidence. Carol Williams’ Halie, the mother, is very present in the opening scenes, but mostly as a nuisance to her husband and a mostly offstage voice. Her return late in the third act is where the character is truly allowed to weigh in, and she effectively renders self-righteousness moving into panic and desperation as her imagined grip on circumstances begins to loosen.

As Vince’s girlfriend, Shelly, Julane Havens beautifully charts our own changing perspective on events and eventually provides the release and hope of escape that makes the bleak scenario bearable. It was engaging work but also a vivid expression of the disquieting horror contained in the text. Barrett Cooper played the younger brother, Bradley, with a distinct physical presence and quality of menace that turned his second act confrontation with Shelly into a chilling and sexually-charged threat that made the intermission that immediately followed a very welcome thing indeed. His choice for a voice initially struck me as caricaturish enough to be at odds with the lumbering and awkward gait (Bradley has a prosthetic leg) and dark, glowering countenance. But as the play evolved, it found a more natural feeling.

Finally, this production gifts us with two performances that make this writer want to search his superlatives with care, so as to not overstate the quality of the work. Bunbury Artistic Associate Matt Orme plays Dodge, the sad and drunken paterfamilias, in a manner that makes you think you simply could not do this material without him. The character’s scabrous sense of humor is crucial to the delivery of the play, giving the audience the opportunity to laugh while swallowing this bitter pill. Mr. Orme can earn laughs with one hand tied behind his back, but it is in the pained moments in-between that this veteran illustrates something much deeper and more resonant, and he brings an epic yet intimate power to his final moments onstage. As the older son, Tilden, Andy Pyle moves about the stage with uncertainty, giving off a glow of unreality that is astonishing and magnetic. It is a portrait of a lost man who has experienced unfathomable tragedy, communicating a deep and elemental pain that the audience can only guess at.

The production design was close to brilliant, with a magnificent set by Lily Bartenstein, lighting by Chuck Schmidt and sound by Maigan Wallace that evocatively brought to life an aging farmhouse. One could feel the wood surfaces made dark by the years of tobacco smoke and lack of sufficient housekeeping – a shelter from reality but also a prison for the suffering souls contained within. The costumes by Teresa Greer and hair and make-up by Thomas Leigh worked perfectly to fit the concept.

Here in the waning days of spring, there are several plays to see in the Louisville area currently, but it would be a shame to miss this dark and bracing dose of American post-modern theatre – the play that some consider Shepard’s finest work. (True West, coming this fall from Actors Theatre, would be one argument for a better one.) Buried Child is a dark and disturbing play, and it may not be to everyone’s taste; but you will not soon again find a better example of the force and quality that this local theatre scene is capable of.

Buried Child

June 8- 24

Wednesday through Saturday 7:30 p.m.

Sundays 2 p.m.

Bunbury Theatre

at the Henry Clay

604 S. Third St.

Louisville, KY

(502) 585-5306