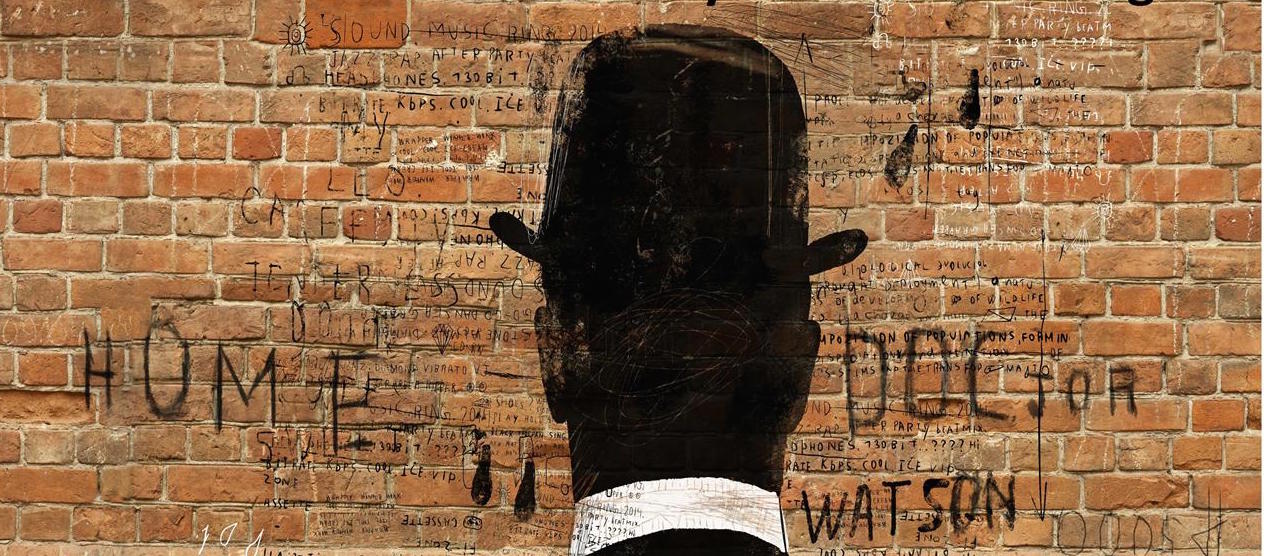

Bruce McKenzie, Ramiz Monsef, Barney O’Hanlon & Conrad Schott in The Glory Of The World.

Photo-Bill Brymer

The Glory Of The World

By Chuck Mee

Directed by Les Waters

Review by Keith Waits

Entire contents copyright © 2015 by Keith Waits. All rights reserved

It begins and ends in silence, yet everything in between is loud, funny, raunchy, violent, absurd. Director Les Waters calls The Glory Of The World, “…a response” to Thomas Merton, an attempt to capture the complexity and perhaps even contradictions found in his life and work. However you choose to describe it, this fourth entry in the 39th Humana Festival is destined to be the most talked about play in this year’s line-up.

As the play begins, a lone figure (director Waters) enters and takes a seat, with his back to the audience, at a simple wooden table. Dressed in black and barefoot, Mr. Waters’s appropriately ascetic presence invites us to consider Merton as a series of titles is projected onto either side of him. This sequence is paced so deliberately that it challenges the audience’s forbearance, but the contrast to what follows is important, and the audience in which I was included was patient and attentive. You could hear a pin drop, and the correlation to Merton’s idea of extended, silent meditation seemed clear.

The action that follows (there is little here that would qualify as plot) is executed by 17 men who have come to a warehouse space to throw Merton a 100th birthday party. A succession of toasts introduces the range and diversity of the characters but also displays a certain alpha-male competitiveness as different claims about Merton’s life and philosophy vie for supremacy. This simple one-upmanship grows as the men sing, dance, lip-synch, drink, eat cake and quote famous people. There is a lot of quotation in the script, most of it quite funny, but the shallowness of the beliefs espoused by the people onstage seems to also be the point. They declare themselves: “Buddhist”, “Catholic”, “Atheist”, “Taoist”, etc., each claiming Merton as one of their own, and recite quotations from a wide range of thinkers and popular celebrities, from Oscar Wilde to Lady Gaga. But original or creative thought seems elusive. All of it seems designed to confirm a lack of depth among the characters.

Their behavior also represents something of a catalog of masculine iconography, and the carefully constructed choreography (courtesy of Movement Director Barney O’Hanlon and Fight Director Ryan Bourgue) is one of the most memorable qualities of this production. An apparent lover’s quarrel early on becomes a tender kiss and then transitions into a delightful tango joined by several other couples. Another scene employs a variety of formal menswear, while yet another erupts into a jolly romp of Charles Atlas bodybuilder poses that prompted a riotous reaction from the audience. These mannerisms are all allowed to achieve intentional and pointed levels of excess, so that by the time we reach the extended, climactic brawl that echoes Fight Club, the Pamela Browne Auditorium is awash in testosterone.

It is difficult to imagine another example of a large cast that seems to be having entirely too much fun onstage. They are Bruce McKenzie, Andrew Garman, David Ryan Smith, Conrad Schott, Aaron Lynn, Eric Berryman, Ramiz Monsef, Barney O’Hanlon, Josh Bonzie, John Ford Dunker, Jose Leon, Joe Lino, Max Monnig, Collin Morris, Brian Muldoon, Blake Russel, and Lorenzo Villanueva. I absolutely will not single anyone out because together they are a true ensemble, passing the focus back and forth like a championship basketball team in dizzying fashion. The final 10-12 minutes that they share on stage is a tour-de-force ballet of physical dexterity and comic brutality.

Playwright Charles Mee and Mr. Waters are playing a bold game here; employing elements that might feel antithetical to the conventional wisdom on Thomas Merton to expand our understanding of his aesthetic. By making the meaning of their work hard to pin down, they break down standard interpretations and the cliché of the monk’s visage that is the common image of the famous mystic.

The whole thing is a scream sandwiched between two whispers, and while the raucous shenanigans of the ensemble repeatedly brought the house down, it is in the bookend sequences that we are clued into the questions the play poses, without providing any resolute answers. The Glory Of The World is purely provocative in the best sense in that it forces us to ponder big questions through highly entertaining, visceral spectacle. It is hugely entertaining but also lingers in memory.

The Glory Of The World

March 20-April 12, 2015

Part of The 39th Annual Humana Festival of New American Plays

Actors Theatre of Louisville

316 West Main Street

Louisville, KY 40202

502-584-1025

Actorstheatre.org

[box_light]Keith Waits is a native of Louisville who works at the Louisville Visual Art Association during the days, including being one of the hosts of PUBLIC on ARTxFM, but spends most of his evenings indulging his taste for theatre, music and visual arts. His work has appeared in Pure Uncut Candy, TheatreLouisville, and Louisville Mojo. He is now Managing Editor for Arts-Louisville.com.[/box_light]

[box_light]Keith Waits is a native of Louisville who works at the Louisville Visual Art Association during the days, including being one of the hosts of PUBLIC on ARTxFM, but spends most of his evenings indulging his taste for theatre, music and visual arts. His work has appeared in Pure Uncut Candy, TheatreLouisville, and Louisville Mojo. He is now Managing Editor for Arts-Louisville.com.[/box_light]