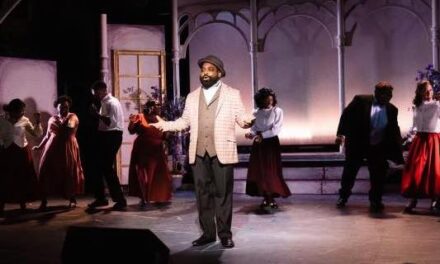

John Rubinstein as Charlemagne in the National Touring Production of Pippin. Photo by Terry Shapiro.

Interview by Scott Dowd. Entire contents ©Fearless Designs, Inc. All rights reserved.

Next month, PNC Broadway in Louisville presents one of the most iconic musicals in the Broadway pantheon. In 1972, as the Vietnam war approached its apex, Pippin set audiences on their heels with its open mockery of the hubris of war. The role of Pippin, the young prince seeking to find his way out of the shadow of his father Charlemagne, emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, was created by twenty-five-year-old John Rubinstein, son of one of the twentieth century’s most acclaimed artists, Arthur Rubinstein, and his wife, Aniela. John’s mother was known for decades as a patron of the arts and, in the years following World War II, a successful fund raiser for relief programs helping refugees from her native Poland. The daughter of conductor Emil Mlynarski, founder of the Warsaw Philharmonic, she was also a renowned chef and cookbook author. John Rubinstein went on to create his own career as an actor, winning the 1980 Tony Award for his role in Children of a Lesser God. He composed the theme music for the critically acclaimed television series Family, in which he appeared for two seasons. He has made hundreds of television appearances and performed in numerous films, including 21 grams and Boys from Brazil with family friend Lawrence Olivier. Rubinstein now completes the arc he began more than forty years ago as he returns to Pippin in the role of Charlemagne.

SD: You had been away from Broadway for about fifteen years when you came back to do Pippin. Was that decision difficult for you?

JR: No, it was very easy in fact. I was in New York doing something else—speaking at my fiftieth high school graduation anniversary celebration—and my agent called to ask if I could get myself to New York. I said, “Hey, I’m already here.” Over the weekend I learned the material, I went in on Monday, and I auditioned for some of my old pals and some new people.

SD: In the show, the metaphor for Pippin is sunrise and, conversely, Charlemagne is described in terms of sunset. What does it mean for you to have completed that arc?

JR: The move itself is not that big a deal. It’s just like playing another role in another play. Playing Pippin when I was twenty-five years old made sense: I was a young man and I fit the part. Now I’m an old man and I fit the role of Charlemagne. Where that does enter in is in doing the show every night! Hearing all that same old music and those same old lines and knowing that it’s a completely different presentation of the show is great fun. I sort of live in two time periods simultaneously. I enjoy that very, very much.

SD: The 1972 production, directed by Bob Fosse, was a bit darker than the current production. Is that a fair characterization?

JR: It is sort of a dark piece. It was written during the Vietnam war and presented at the height of that conflict. So the political/war section of the play, when Pippin wants to follow in his father’s footsteps and be a warrior to fight and destroy the Visigoths, is a comedy number no matter how it is staged. But when the Vietnam war was raging, it landed on the audience in a much deeper and more personal way than it does now. The fact that we’re again and still at war means less nowadays, simply because we are not involved in it. There isn’t a draft as there was back then, where every family was involved in some way. Either they had a kid who might be drafted and was desperately trying to keep his college deferment, or they literally had kids, or fathers or brothers, who were serving in Vietnam, killing people and at risk of being killed. The entire country was involved in that war; we felt it and thought about it every single day. All of us did, all around the country—Democrats and Republicans, North and South, East and West. When we came out on stage making fun of war, it was a blood-curdling thing. And the audience responded accordingly.

SD: I am younger than you, but it seemed like the war was constantly on television.

JR: It was on all three channels every single night. We watched the Vietnam war like we watch basketball right now. It was ubiquitous. We saw our guys napalming people and we saw villages burning and we saw fleets of helicopters dropping bombs. We saw tunnels where Vietnamese villagers lived and watched American soldiers uprooting those tunnels. We watched that war like it was a soap opera, like a serial. But now we do the war scene and the audience claps for the acrobatic acts and laughs at the jokes but…yes, it was darker then.

SD: You mentioned Pippin’s desire to follow in his father’s footsteps. Charlemagne is, of course, an iconic, historical figure—emperor of the Holy Roman Empire—and Pippin has to try to measure up. When you were playing Pippin, did you feel any of that in relationship to your own father?

JR: Yes. I have to say that with any role you play, you bring as much as you can of reality and your real life to it. In those same years that I played Pippin, I also played rapists and arsonists, murderers, child molesters, etc. I didn’t have a lot of experience doing those kinds of activities. But if you are supposed to kill five people in cold blood, you have to find it yourself somewhere. You ask, “When was I that angry?” Or make it up—it doesn’t have to be from your actual experience. You ask yourself, “Where would that kind of anger or coldness come from?” That’s what an actor’s basic job is: to find inside of himself where that could come from and portray it believably. So when I was playing the son of a very famous, powerful father and trying to impress him and trying to make him proud of me, that was easy. That was my life. My father was a one-of-a-kind iconic, great artist who was renowned and revered in those days. I was just a kid. I was a musician and I was an artist, too—but on my level. They were very different worlds. I never felt competitive; I never felt I had to become the same kind of icon he was. But I did grow up around a very high quality of performance and approach to your art. That made me aspire to aim for the same kind of targets even though I was quite comfortable in accepting that I was probably never going to hit it. That never really caused me any pain.

SD: Your mother was also a formidable character in her own right.

JR: Absolutely.

SD: You play the piano and compose. Do you also cook?

JR: I do a little bit. My mother was a real cook. My two sisters and my brother are all amazing cooks. Of the four of us, I am the least proficient in the kitchen. But I do love eating and I do make some of my mother’s food. Fortunately, she wrote a cookbook so we all have her recipes.

SD: You probably don’t have the facilities to do much cooking right now. Has it been hard for you getting back on the road?

JR: Not really. I enjoy it. It is an adjustment because we move every week. We have a few stays of two weeks and had three-week sit-downs. Every Monday night we arrive at a new place and Sunday night we pack it up. It’s just a routine that is different from living at home and coming into your own kitchen every night. It’s an interesting and wonderful way to see the country.

SD: You have a large family and have always made time in your career to be with them. How does your being on the road affect your wife and kids?

JR: I do suffer from not being around my lady and my kids. Two of my boys are in college in Chicago. We have been zigzagging across the Midwest all winter long, so I’ve actually seen them quite a bit considering they are away at college. Max is nine and the only one still at home. I was able to be in L.A. for his ninth birthday. He has joined me in several cities, so I’ve seen him and his mom a lot.

SD: When did you make that decision to become an actor?

JR: I was about eleven or twelve. I went to a school in New York City that took its public speaking and dramatics very seriously. It was run mostly by British teachers and the Brits take all that stuff way more seriously than we do in this country. They believe that it is good for young kids to perform, to speak publicly, to recite poetry, to learn lines, to sing and even to whistle. The eighth grade graduating class performed one of Shakespeare’s plays every year. It was an all-boys school, so the boys played the women’s parts.

SD: Very traditional.

JR: Just as in Shakespeare’s day. In seventh grade you learned and studied the play you were going to do in the eighth grade. Your homeroom teacher was the director. In my case, he was a great young pianist, composer, actor and mathematician. In sixth grade I was in The Tempest, playing one of the fairies; in seventh grade I played “the boy in Henry V,” which is actually a good little role—he has a wonderful monologue. Standing alone on the stage, he wonders if he should go to war or not. Coincidentally, it was an early Pippin moment. Then in eighth grade our class did Macbeth and I played Macbeth. By then I knew that was what I wanted to do the rest of my life.

SD: Some people believe that Pippin is completely alone on the stage and that all of the characters we see are just parts of his own psyche. What kinds of choices have you made for the character of Charlemagne that give him dimension?

JR: Diane Paulus, who directed this incarnation of the play, was adamant about all of the people in the play having a character who is a circus employee. We are a traveling circus, as opposed to being a traveling troupe of Commedia del Arte players. Each of us has a role in the circus.

SD: What part do you play in the circus?

JR: I am the knife thrower. My character and all of the others have a backstory that explains how we joined the circus and describes our lives before becoming a member of the troupe. We had to do an exercise in which we created the lives of these characters and performed them for each other. It was traumatic, but instructive. I loved it—ultimately. I resisted it at first but, eventually, embraced it.

SD: What made you change your mind?

JR: Mostly, it was watching everybody else do their exercise. It brought us together and added levels to the performance. At one level I am John Rubinstein playing Charlemagne, the lusty, goofy father of the title character in Pippin. That character is more interested in sex and killing than he is in his son. He is a tyrant and lusty old man who can have any girl he wants, can have people killed if they displease him. We meet this guy who is all-powerful and, yet, he can be manipulated by his wife’s sexual power over him. I play him and the guy who is the circus performer who is doing this for another set of reasons. He has his real relationships with the people in the company that are completely apart from Charlemagne’s motivations and different from the relationships the emperor has with characters on that tier. It’s a very interesting and challenging job to do the play in this way.

SD: There is a moment, just before Pippin “assassinates” Charlemagne, in which the emperor gives what appears to be genuine fatherly advice. What choices have you made about playing that?

JR: Well, for those who haven’t seen Pippin, I don’t want to give too much away, but there are many layers to this play. There are certain nexus points at which the harmonics of the layers create an overtone that is not part of any one layer, but a combination of them all. There is a “reality” to the play; it is sort of pretend and reality simultaneously. It is very Pirandellian. On one level it’s John and Sam—the actor playing Pippin. We’re on the road and currently in Naples, Florida. It’s 2015 and we’re doing the national tour—that has a reality to it. In the next reality, I am playing a knife-thrower and have my own backstory. I’m working with this circus company and my job is to get this kid who is pretending to be Pippin to burn himself up in the grand finale so that we can get money for the circus tonight. So I have a prescribed role that I must serve: to show him war and how brutal it is so that he will hate it and turn to something else. I also need to show him my politics so that he will rise up against me and to manipulate him into killing me so that he becomes king and is forced to deal with all the political problems and become discouraged. That’s my job: to make him hate war, be disgusted by my debauchery, and be broken and disappointed by his inevitable failure as a political leader. On the third level, I play Charlemagne, the father of this young boy, and I let him come to war because he wants to and he makes me proud. But then he disappoints me because he doesn’t do well in battle. I am then manipulated by my wife to be vulnerable to him as he sneaks into the cathedral at Arles in order to kill me. He gives me a chance to apologize—to change his mind about that—but I don’t. My character is vitriolic, self-aggrandizing and unapologetic in an effort to force Pippin to kill him. On that level of the play my character doesn’t think he has the guts to do it, and when he does Charlemagne is astounded and dies amazed. The character in the circus troupe, on the other hand, has gotten exactly what he wanted. He has angered and manipulated the Pippin actor—so I’ve done my job.

SD: Maybe because it is so popular as a school play, people misread Pippin as a simple, lightweight show.

JR: I agree. It’s a very deep show. It’s about our inner life and our opinions of ourselves. It’s about how we all, at some point or another, yearn and hope for the ability to live a life that is meaningful. In America, that still often means to make money and be rich and famous. But it isn’t about that. This is more about feeling that you matter, that there is a reason you are on this ride called “life.” It’s about that desire we have to do something with it that will be important. Then, as we go through our lives, we might have our flashes where we feel, “I’m on to something here. This is important and valuable.” Then we have other moments during which we feel like, “Ach! This is a waste of time. I can’t do what I thought I would do…I’m a waste.” The rest of the time we go forward like we’re in a blizzard, you know? We know we have to go forward, but we have no idea where we’re going or why we are doing it. “Eat dinner, now sleep, get up, do what people tell me to do, go to sleep again…and don’t forget breakfast.” That’s pretty much what we do sometimes—for long expanses of our lives. Finally, what does it all add up to? What’s it all about? That’s what this show is about.

You can see Pippin June 2-7 at The Kentucky Center for the Arts. Call 502.584.7777 or go to kentuckycenter.org for tickets. Subscriptions for the 2015-2016 PNC Broadway in Louisville series are on sale now. A five-show package begins at only $155 per person. The season opens in September with the popular Rodgers and Hammerstein musical Cinderella. The season also includes Cabaret, Dirty Dancing and Motown the Musical as well as the return of Phantom of the Opera. Season extras include Wicked and Disney’s Beauty and the Beast. Click on louisville.broadway.com for tickets and more information.