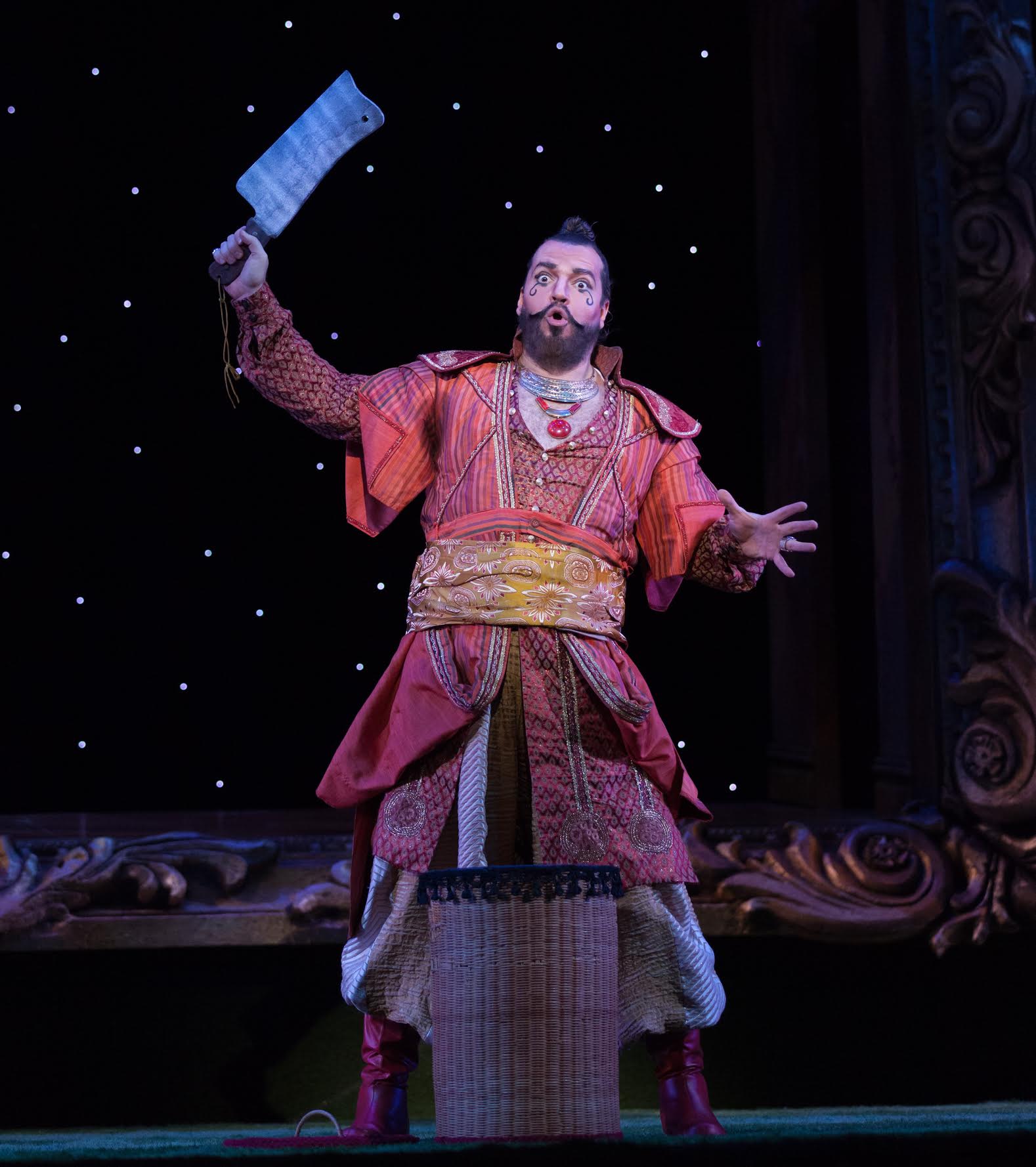

Riker Hill & Stephen J. Koller in Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead.

Photo courtesy The Alley Theater.

Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead

By Tom Stoppard

Directed by J. Gregory Sanders

Review by Cristina Martin

Entire contents copyright © 2016 Cristina Martin. All rights reserved.

To begin with, there was the weather. A discomfiting, anticipatory heaviness hung in the air on Thursday night. The afternoon’s brutal downpours had given way to a brightness too good to be trusted; sure enough, before anyone got too comfortable, a new wave of violent and vociferous storms rent the heavens.

How apt that this arbitrary atmospheric diatribe should be audible inside The Alley Theater on opening night of Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. If the weather was unsettled and unsettling, the performance was equally, brilliantly so. The raging storms provided a perfect, if unintended, soundtrack to a play that’s meant to unseat us: to turn the world of actors and playwright and audience on its head, to make us scramble to keep up with the existential questions it poses, and to prevent us from ever becoming complacent because we think we’ve got it all figured out.

Lucky for those who didn’t want to get wet, this wasn’t Shakespeare in the Park. It was Shakespeare only obliquely — by the wayside, if you will, or inside out. Taking two ancillary characters from Hamlet and giving them their own show, so to speak, with Shakespeare’s play in the background, Stoppard deconstructs the whole theatrical enterprise, literally and figuratively. Rosencrantz (Riker Hill) and Guildenstern (Stephen J. Koller) first appear wandering across a dark stage, trying hard to remember where they’re supposed to be heading and who sent for them. They flip a coin repeatedly, and it continues to come up heads. Rosencrantz accepts the result with equanimity (he’s been winning the coin tosses), while Guildenstern tries to work out rationally how 91 heads in a row could be possible according to the laws of the universe.

Mr. Hill and Mr. Koller are well cast and excellently matched. Guildenstern’s hard, cerebral quality is balanced beautifully by the sweetness that radiates from Rosencrantz. The two keep up a near-constant verbal volley and make it seem effortless, which is far from easy to do. Part of what makes Stoppard’s play a delight to behold is that he gives language itself such a prominent role, constantly playing with rhythm and meaning, letting it break down from time to time or devolve into the absurd to underscore its limits. This cast wields words with skill. I couldn’t help wishing, however, that they’d slow down just a hair to allow the full meaning and wit of the dialogue to come across.

En route to what they figure out is where they’ve been summoned (the royal Danish court in Hamlet), Rosencrantz and Guildenstern encounter a troupe of traveling actors. Here’s where things get really interesting. These Tragedians are a motley crew, ready to be just about anything you’d like them to be for a coin or two. They’re led by The Player (Joey Arena), an arresting fellow whose glib pronouncements send our heads spinning as to who’s an actor, who’s a spectator, and what the worlds of plays within plays say about the players, the characters, their creators, and us. Mr. Arena lends The Player just the right amount of smug bravado to lead us to believe he might be the one engineering the course of events here just a little bit… but then, maybe it’s all just an act. The ragtag troupe is colorful and energetic, their vaguely Renaissance costumes looking exactly like what you’d imagine an itinerant bunch of actors might wear. As the Tragedian Alfred, Anna Shelton has some priceless facial expressions and physical bits that garner good laughs.

The costumer for Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead is faced with the challenge of costuming actors who are more often than not playing actors, and Hannah Wold does a very nice job. The bright capes of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern (blue for Rosencrantz, red for Guildenstern) are echoed by the capes worn by Player Rosencrantz (Josh Farley) and Player Guildenstern (Maxwell Williams) when the Tragedians portray the duo. As Mr. Hill and Mr. Koller move about and gesticulate throughout the evening, each man’s cape slips a bit such that it ends up draping his left shoulder at a rather rakish angle, a parallel asymmetry that adds visual interest and reinforces a pervasive mood of disequilibrium.

At one point, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern learn about their own fate by watching what befalls Player Rosencrantz and Player Guildenstern in the Tragedians’ portrayal. Doesn’t theatre often show us ourselves in the characters on stage? Then again, are we not all players, for “All the world’s a stage…”? Might there be some great playwright in the sky who knows how it all ends, or are we players engaged in writing our own scripts? As the implications hit and set our wheels turning, the show can feel like encountering funhouse mirrors and M.C. Escher staircases at every turn.

A handful of the characters we encounter on stage from time to time function only in the plane of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, to wit: Hamlet (Spencer Korcz), Claudius (Francis Whitaker), Gertrude (Janice Walter), Polonius and the English Ambassador (both played by Josh Rocchi), and Ophelia and Laertes (both played by Clare Hagan). These actors all manage to acquit themselves of their Shakespearean roles with a subtle wink, indicating they know that we know that they know what they’re playing at. Mr. Korcz seems literally to fall over himself in troubled melancholy, while Mr. Whitaker summons Claudius’ kingly gusto with aplomb. The king and his new wife, Hamlet’s mother Gertrude, appeal to the characters Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, erstwhile friends of Hamlet, to discover the source of Hamlet’s melancholy.

Not sure how to go about this charge or whether and how to take action, Rosencrantz says, “I feel like a spectator!” Guildenstern replies, “What a fine persecution — to be kept intrigued without ever quite being enlightened!” He speaks for anyone who’s ever felt unsure as to what’s really going on and how to proceed, either in a specific situation or in an existentialist sense. But it’s as though Stoppard is putting words in our mouths, too, as we try to make sense of his play. The barrage of clever words and ideas happens at such a rapid pace that spectators can’t process it all nearly fast enough. We feel off-kilter because we’re struggling to keep up; once we’ve absorbed it all and had time to reflect, we feel off-kilter because there’s not simply one neat and tidy gem to take away. It calls into question more than it answers.

This would make for a rather bleakly confusing persecution indeed, were it not for Stoppard’s humor, born from delightful word play. As part of a plot point in Hamlet, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern find themselves sailing to England on a boat toward the end of the play.

Rosencrantz: Do you think Death could possibly be a boat?

Guildenstern: No, no, no… Death is “not.” Death isn’t. Take my meaning? Death

is the ultimate negative. Not-being. You can’t not be on a boat.

Rosencrantz: I’ve frequently not been on boats.

Guildenstern: No, no… What you’ve been is not on boats.

We may not be sure which end is up, but we can always take delight in language and its ability to electrify the brain like a streak of lightning. Stoppard’s play is a comedy, after all. Confusing and unsettling as the questions it poses can be, sometimes we’re just meant to sit back and laugh. This production invites us to do that, even as we’re still piecing together what it all means.

Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead

June 23 – July 9, 2016

The Alley Theater

633 West Main Street

Louisville, KY 40202

(502) 822-5598

www.TheAlleyTheater.org

A lover of the arts in every form, Cristina Martin has a background in theatre, dance, and classical music. A native of Chicago, she currently lives in Louisville with her husband, three active young boys, two rambunctious dogs and a cat as old as the hills.