Confront – Vinhay Keo

Moremen Moloney Gallery

Review by Keith Waits

Entire contents copyright © 2017 Keith Waits. All rights reserved.

Louisville has a thriving visual arts scene, but it lacks a meaningful representation of installation work with the artist’s personal involvement. It happens in other cities, but most exhibition spaces here tend to traffic in fairly traditional presentations. Academic galleries tend to come closest to fulfilling this need, but even they offer such programming intermittently.

Vinhay Keo is only a little more than a year out of the BFA program at Kentucky College of Art + Design at Spalding University (KyCAD), and Moremen Moloney Contemporary Gallery is hosting his first solo exhibition, Confront. The Cambodian-born artist here follows up on his work from the school’s 2016 BFA exhibit, some of which is included here.

Like many artists at this age, Keo is preoccupied with identity. His experience of moving to Bowling Green Kentucky and searching for a place in a smaller American community is realized through a monochromatic aesthetic in which the artist is continually surrounded, nay, overwhelmed by the color white. The Moremen Moloney environs, a renovated home, provide  an interesting format by forcing the elements into individual rooms. Keo himself stands in the center of the first room on the left, motionless and silent, naked from the waist up, his lower half wrapped in white fabric and his neck adorned with a stiff white collar from which emerges a long white tie. The tie transitions from broadcloth to a twisted cord that reaches out of the room, across the hall and into the opposite room, where it disappears into an enormous, multi-peaked mound of confetti that is, of course, white.

an interesting format by forcing the elements into individual rooms. Keo himself stands in the center of the first room on the left, motionless and silent, naked from the waist up, his lower half wrapped in white fabric and his neck adorned with a stiff white collar from which emerges a long white tie. The tie transitions from broadcloth to a twisted cord that reaches out of the room, across the hall and into the opposite room, where it disappears into an enormous, multi-peaked mound of confetti that is, of course, white.

The hallway displays photographic images printed on aluminum, five of which are specifically created for Confront, and several others that are from his time at KyCAD and the BFA exhibit. In the live installation, Keo’s brown skin is rich and warm in contrast to all of the white. The interior décor is analogous to the austerity of Keo’s imagery, and he has dusted his natural skin tone with white powder on his shoulders.

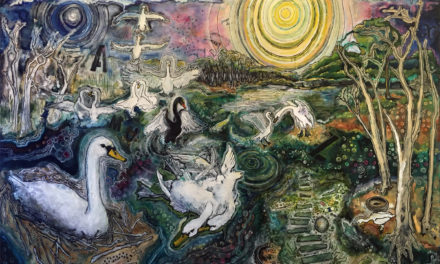

In the photographs, Keo is mostly covered in white make-up, even graying his black hair, or wearing white clothes. His mouth emits viscous white fluid filled with suggestiveness, and in the most striking picture, he appears to vomit a profusion of confetti.

We can draw from all of this that Keo has spent an inordinate amount of time and energy trying to fit into a Caucasian world and that the effort very likely confused the artist’s own sense of himself, his own individual identity. Subsumed by a culture of Bible-belt social mores and backyard barbecues, and with, what we must presume, was a surfeit of similarly brown-skinned neighbors, what degree of denial and willful ignorance must have colored Keo’s own view of himself?

That quality of isolation is pointedly conveyed in this performance installation, set as it is in a high-end exhibition space that draws a well-to-do, predominantly white audience. As Keo stands, stone-faced, the viewers move around him sipping wine and blithely commenting on the artist and his work as if he weren’t within earshot. Is this a replication of Keo’s early life in Bowling Green? The Cambodian boy as the Other? Not fully a citizen and therefore not deserving of full social embrace? If so, Keo has provocatively forced the viewer to be complicit in realizing his statement.

The expression of his thesis is highly intellectual, but the imagery is emotionally charged. And if one stands in the room with Keo, listening to the self-satisfied chatter surrounding him, it is not difficult to empathize with his position. We might expect an artist coming from this experience to put forth a message of protest; to plant his feet and demand recognition for who they are and not who society forces them to be, but Keo codifies his biography into a savvy recognition of his repression.

The expression of his thesis is highly intellectual, but the imagery is emotionally charged. And if one stands in the room with Keo, listening to the self-satisfied chatter surrounding him, it is not difficult to empathize with his position. We might expect an artist coming from this experience to put forth a message of protest; to plant his feet and demand recognition for who they are and not who society forces them to be, but Keo codifies his biography into a savvy recognition of his repression.

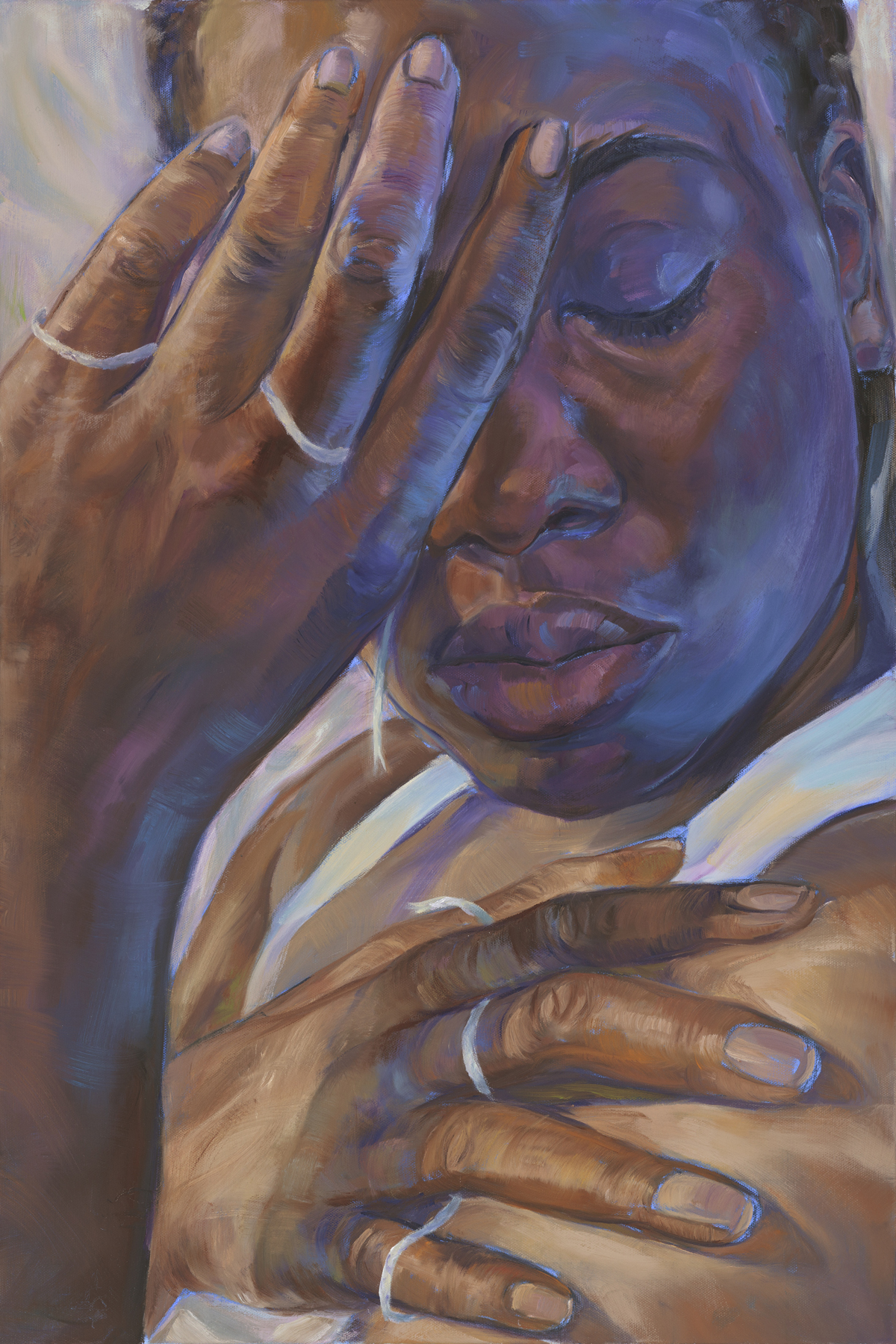

This reading is reinforced when we consider that Keo is Gay. While it doesn’t seem the most important aspect of Keo’s projected alienation, at least not in the context of this installation, he references another level of repression in a covert photographic image in which he blocks the view of his genitals with his hands, his entire body, of course, covered in white.

Keo has made clear that the overabundance of shredded paper makes reference to the relentless documentation of personal history in the United States. How many bureaucratic forms has Keo filled out in his journey thus far? We are all burdened with such baggage, and it is now a largely digital repository of personal data, but Keo’s paper trail is undoubtedly greater than that of most law-abiding native-born citizens.

As personal as the entire project is, it also strikes a universal chord for all immigrants who come to America as People of Color and/or people for whom English is a second language, and perhaps many others who might not as easily match those descriptions. This positions Confront as one of the more important exhibits of the moment, a commentary that speaks to the chaos in American society, the worth and importance of the immigrant in that chaos, and the very core value of diversity that lies at the heart of the United States of America.

Confront -Vinhay Keo.

September 15 – October 14, 2017

Installation & Performance with artist talk:

October 13, 6 – 8 PM (Closing Performance)

Moremen Moloney Contemporary Gallery

939 East Washington Street

Louisville, KY 40206

moremenmoloneygallery.com

Keith Waits is a native of Louisville who works at Louisville Visual Art during the days, including being the host of PUBLIC on WXOX-FM 97.1/ ARTxFM.com, but spends most of his evenings indulging his taste for theatre, music and visual arts. His work has appeared in Pure Uncut Candy, TheatreLouisville, and Louisville Mojo. He is now Managing Editor for Arts-Louisville.com.