Diane Kahlo, Mandala installation, 2018, mixed media

Merton Among Us: The Living Legacy of Thomas Merton

By Keith Waits

Entire contents are copyright © 2019, by Keith Waits. All rights reserved.

Thomas Merton died 50 years ago, but his life and writings still exert a powerful influence over people’s lives, and his death coincided with the rise of alternative spiritual context in modern society. He is often now embraced for the cosmetics of his individual message; a copy of “The Seven Story Mountain” lending the pretense of deep thought when carefully placed on the coffee table for maximum, casual exposure.

Merton has been represented in art for both his authenticity and for that superficial social status. A new exhibit, Merton Among Us: The Living Legacy of Thomas Merton allows a select group of artists and thinkers to both respond to the Catholic priest and Trappist monk and to fashion a highly personal context for a ruminative gallery experience.

Carlos Gamez de Francisco, “Girl in Mantilla”, 2018, chromaluxe aluminum print, 45″ x 30″

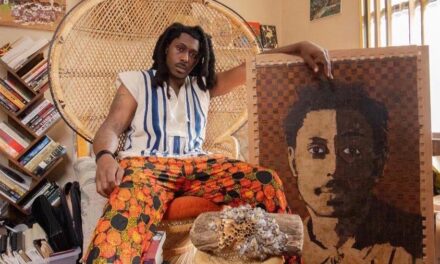

Although there is significant textual material, the initial impact is from visual art both primitive and sophisticated in its aesthetic. Steve Armstrong’s “Reluctant Angel” carved wooden sculpture illustrates the clarity of Post Modern primitivism, standing in contrast to Carlos Gamez de Francisco’s “Girl in Mantilla”, which imposes the trappings of Latin/Catholic iconography on a child in a photograph so sharply brilliant in detail and romantic in its lighting that is seems a world apart from the Armstrong piece.

Yet they are both conjuring up religious imagery that touches upon Merton’s journey from stifling religious ritual to a more inclusive relationship to God, and his contemporary status as a figure that bridges time and denomination. The tidy turns and alcoves of the 849 Gallery lend themselves to encountering the art in reclusive postures so that the space provides an inherently ecclesiastical architecture for the exhibit. That there are no labels for the work underscores the importance of approaching each piece on individual terms. Diane Kahlo’s oversize painted portrait of Merton is positioned on the far side of the gallery, within one of the alcoves, so that you must come at it in a very specific alignment as if coming to confess your sins.

This foundation is joined by two installations deliberately formal in their religious aspect, a Mandala arrangement from Kahlo that dominates the atmosphere of the most open part of the space, and another directly in opposition by Joe McGee in collaboration with quilter Penny Sisto, “The Mother Figure Learns of Merton’s Death.” Together, these pieces lead but never force us through the space in a silent contemplation worthy of Merton’s teachings. I am certainly no scholar of his work, but it seems inappropriate to rush through this environment, and that seems a fair reflection of the man.

have you seen the widow’s photographs

of sunrises and sunset taken near the yellow silos?

and of bumblebees asleep in the asters?

how at the core of a Louisville winter day is silence:

how sun sifts earthward quietly earthward quietly as a monk’s prayer

like coins sieved through ashes.

– from “Kentucky Winter” by Maureen Morehead.

Steve Armstrong, “Vacant Chair”, 2017, carved & painted wood, 24″x 18″x 3.5″

Those feelings are reinforced once we read through the significant amount of text from several individuals, some, if not all, of who either knew Thomas Merton personally or have evidently studied his writings in some depth: Dianne Aprile, Owsley Brown III, Nana Lampton, Maureen Morehead, Paul M. Pearson, Rev. Al Shands, and Frederick Smock. That these words are presented on digital screens was slightly disconcerting. The choice of format may be current and efficient, but there is a greater impact in meeting these elements in the printed catalog (available for purchase) than a glowing monitor, and one of the greatest treats of the exhibit is a case containing personal correspondence between Merton and Coretta Scott King; thoughts shared between the wife of Dr. Martin Luther King and “A White Liberal” that resonate even when contained on the yellowing paper of a Western Union telegram.

Some of the connections to Merton may seem slight. Would we ever think of him in relation to Carlos Gamez De Francisco’s dark and sumptuous photographs if we encountered them outside of this specific context? Or Tom Pfannerstill’s painstakingly carved recreations of discarded commercial packaging? How could an empty, flattened container for Tide detergent possibly speak to the spiritual life of Thomas Merton?

For those, like myself, who are not sufficiently educated on the life and teachings of the man, we are helped immeasurably by the context provided by the curatorial team that includes Joyce Ogden, Hunter Kissel, Kevin Wilson, and Andrew Cozzens. We read that Pfannerstill’s objectification of trash is both, “meditations made concrete” and the “vicissitude of a common object”; an insightful connection between process and theme that reflect Merton’s consideration of humanity’s place in nature. Gamez de Francisco’s images provide a crucial balance in scale and color within the overall exhibit, and if his thematic connection seems more tenuous, I think the featherweight touch of Catholicism here is important.

More obvious is the inclusion of Laura Lee Brown’s photographs of “Northern India”, “Cambodia”, and “Tibet”, which provide physical geography for Merton’s identity as Eastern Mystic – he died in Thailand shortly after a meeting with The Dalai Lama.

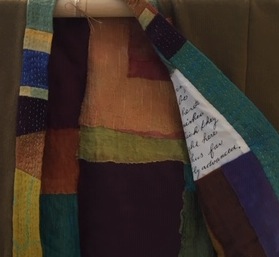

Vallorie Henderson, “What’s Old is New” (detail) 2018, hand-dyed Merino wool scraps with remnants from Sergeant First Class Robert L. Henderson’s World War II U.S. Army blanket, hand stitching, 48″x53″

The tactile feeling of Vallorie Henderson’s hand-dyed and felted Merino wool has the ability to pull us out of the comfort and security of the gallery and gift us with a crucial touch of the natural world. Signs instruct us not to touch the art, and they are necessary because much of the work here is enticing in its visceral, real-world presence. Would Merton approve of such imposed restriction? Or would he welcome us to touch the wiry but soft surface of Henderson’s hand-made felt, and feel the careful balance of solidity and delicacy in Armstrong’s carved wood. Certainly, Kahlo’s shrine-like arrangement fairly demands we humbly kneel, if not in supplication, then at least in modesty.

And revisiting the question of those digital screens, they do accomplish the task of positioning the written word elements in equal relationship to the visual work, lending them physicality in the space that printed matter might lack. But the textual material helps Merton Among Us reach past the easy trend or faddishness to help illuminate the authentic foundation of Thomas Merton’s work and influence.

Merton Among Us: The Living Legacy of Thomas Merton

October 5, 2018 – January 18, 2019

Thursday & Friday / 11:30am – 2:30pm

or by appointment / acozzens@kycad.org

849 Gallery at KyCAD

849 S. Third Street

Louisville, KY 40203

KyCAD.org

Keith Waits is a native of Louisville who works at Louisville Visual Art during the days, including being the host of LVA’s Artebella On The Radio on WXOX 97.1 FM / ARTxFM.com, but spends most of his evenings indulging his taste for theatre, music and visual arts. His work has appeared in Pure Uncut Candy, TheatreLouisville, and Louisville Mojo. He is now Managing Editor for Arts-Louisville.com.