Interview by Katherine Dalton

Entire contents are copyright © 2020 by Katherine Dalton. All rights reserved.

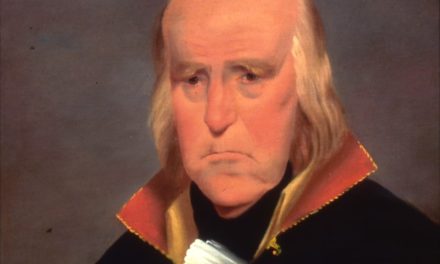

Gwynne Tuell Potts is a historian, Louisville native, and the former executive director at Locust Grove, the final home of Louisville founder and Revolutionary War hero George Rogers Clark. Her new book, George Rogers Clark and William Croghan: A Story of the Revolution, Settlement, and Early Life at Locust Grove has recently been published by the University Press of Kentucky. She was interviewed by Katherine Dalton.

This is the second of three parts.

Q: George Rogers Clark made his name when he was a young man—but his life also took a tragic turn early. Please talk about that.

Potts: He was what—25, 26, 27—when he accomplished the things we remember. Think about that with our own children, with our own lives. That’s remarkable. Washington sometimes received so much advice from his generals that he was paralyzed. Clark, on the other hand, was on the opposite side of the country trying to prevent British assaults from New Orleans, from Detroit, aimed at storming through Kentucky and up the Ohio to Fort Pitt and from there to Philadelphia. He essentially was alone in all his planning. He was untrained in anything except surveying. He had good manners, a natural charisma, and a few Virginia connections, but that [last] gave him a little more than letters of introduction, and from Patrick Henry, some gunpowder. He was 850 miles away from Williamsburg with about 170 men who were less able than he.

And if that weren’t enough, he had to win over as many Native American tribal chiefs as possible to try to end the raids into Kentucky, while at the same time he was figuring out how to secure the loyalty of the French population that inhabited [what is now] Illinois and western Indiana. And finally, he had to keep the wildly independent Kentucky settlers happy.

He had an impossible job. And to add just a little more stress, from the very first moment of the creation of the Illinois expedition, Patrick Henry’s covert objective was the British fort at Detroit. At that moment the British fort at Detroit was undergoing improvements. And money? Clark spent all of the income he earned serving in Kentucky in 1775 and ’76, and ran up credit bills that he never was able to fully satisfy, just to keep all of this afloat.

At the end, when Washington and Jefferson finally gave him the green light for the Detroit campaign, and the Pennsylvania militia was following him down the Ohio from Fort Pitt, they were captured and massacred by a Detroit force led by Joseph Brant. Clark was 29 years old–and it was over. His service wasn’t needed any longer. He didn’t want a political future; he respected almost no one who was a politician except, of course, Jefferson, his idol.

And not only was he broke, I would suggest he was broken. He began to develop chronic poor health, some sort of rheumatoid condition, and I would think also he was suffering from PTSD at that point, which was unheard of then. I would say all of these issues are contributing factors to his collapse at the age of 30.

Q: The Revolutionary War years and the subsequent period of Kentucky settlement was a harsh era, and modern readers might blanch at much of brutality you chronicle in this book—including the way Clark executed some Native American warriors captured at Vincennes. Yet it is clear Clark was an able negotiator with various tribes, including the formidable Shawnee, and had their respect. What is your opinion of Clark’s dealings with the Native Americans?

Potts: His relationships with Native Americans were mixed. He lived in times of upheaval, and behavior was as erratic as the times. I understand what you mean about the book’s brutality. I didn’t think of it as a brutal story when I sat down to begin it; I was going to write two simultaneous biographies. But when the narrative brought them finally out of the frontier war into settlement, I literally took a breath. It was as if I’d been writing in a cave and suddenly emerged into the light. The fighting was finally over. If it was a physical experience for me, what must it have been for them? But you can’t tell the story without that.

As for the Native relationships, one source for this is the journal of Ebenezer Denny, who was an army officer and a chronicler who spent a great deal of time with Clark during the 1785-86 federal Indian Commission conference near what is today Cincinnati. Denny wrote that when Clark was present at the conference, the great warriors never noticed any other general. And he also noted that Clark rose and met each of these men with an embrace. I think this is interesting, particularly when you learn that when the conference was over, the Shawnee nation essentially was defeated, on paper—they weren’t defeated in reality yet—and their chief, Moluntha, begged the Americans to have pity on their wives and children, because he knew what he had just signed.

Six months later, while Clark was leading the ill-fated second march to Vincennes, he allowed Ben Logan to go collect his militia and come through Chillicothe, which was the Shawnee capital, back to Vincennes, which resulted in a little battle and Moluntha’s death. They arrested Moluntha’s wife, Nonhelema, who was the great Cornstalk’s sister. But when Clark and Richard Butler and Daniel Boone learned this, they made arrangements for Nonhelema’s release from the prison in Danville, restored her status as an American patriot, and had her moved to safety in Detroit.

So you take this, and then you look at Vincennes in 1779. I had to try to balance that, too. A lot of Clark’s military behavior was affectation. It was a form of posturing. He was a farmer’s son with no military training, and so he read British pamphlets to learn how to negotiate with Natives, and he used his wits to confuse and astound if not confound his enemies. This is all he had.

When we get to the 1779 execution of the Vincennes Natives, I think we have to look at two reasons. First, he had been genuinely shocked by the Native-British massacres that he witnessed in Kentucky in 1777. I’m not sure he ever recovered from that. He genuinely wanted revenge. And remember that the Natives had arrived at Vincennes carrying Kentucky scalps.

Secondly, he had developed an almost visceral understanding of what he considered to be Native thinking. His instincts and his experience taught him that Native Americans respected strength. And to execute the Natives that Henry Hamilton had sent to Kentucky to kill the settlers would leave no doubt as to which man was the stronger. It was going to be Clark.

Now we move ahead to the 1780 Chillicothe campaign, which ended with the Kentucky militia committing several atrocities. The men involved in that excused their behavior as retribution for equally atrocious actions taken against the settlement outposts, and the fact that they had just witnessed the Shawnees putting their captive militiamen to the stake before they left Chillicothe. It was all awful: the murder of the Moravian Indians, the “baking” of Colonel Crawford, the massacre at Yellow Creek, the death of Boone’s sons; it was all horrific and it was all conducted in the name of retribution, which is the story of the frontier wars in the Ohio River Valley. But, as I said, if these stories aren’t told, a reader isn’t going to understand the trans-Appalachian American West or, more to the point, George Rogers Clark.

There’s no single characteristic I could find to define his relationship with Native Americans. When he was at war, he fought as a warrior against his enemy, whether that was British Governor Henry Hamilton or Joseph Brant or Benedict Arnold. He fought instinctively, and that’s really all I can say about it.

Q: Over the year’s Clark’s reputation has suffered from accusations of immoderate drinking or even alcoholism. What is your opinion?

Potts: There’s no doubt he was a binge drinker. He apparently drank at specific times during specific periods of his life to drown out various problems. He went on some fantastic benders. They’re recorded. Was he an alcoholic? Maybe not.

He was ill in 1785, but the Kentucky militias didn’t want anyone else to lead the 1786 Second Vincennes campaign, and Ben Logan assured the governor then that Clark had fully recovered from what, I don’t know, maybe his first major bender? I’m not sure. Richard Butler reported that Clark was moody and emotionally uneven during the Indian conference, but Denny’s journal, which is the best record of the conference, including Clark’s behavior, recorded absolutely nothing to indicate he saw a problem. Clark injured his left leg about this time–he probably broke his ankle. It was never set and never right again, and he used a cane from his early thirties to compensate for this injury. This left him with an uneven gait and apparently lifelong pain. Yet he considered himself to be fit enough to found a Spanish colony in 1788 when he was 35, and he was able to lead, in his mind, a French campaign that he hoped would dislodge Spain from New Orleans in 1794 when he was 41. He walked a little goofy and he was in pain, but he still thought he had the goods.

His nieces and nephews remember their visits to his Clarksville house with fondness. One of his nephews—one of Fanny’s sons—was taken to school every day on the back of Uncle George’s horse. Would she have put her son on the horse if her brother were recovering from a bout of drinking? I doubt it. There’s not a single contemporary family letter in existence that mentions Clark’s drinking. Thirty to fifty years after his death, great-nephews told the story in Lymon Draper [who wrote an unfinished biography] that they had heard Clark may have been a drinker, but by then his reputation had been negatively impacted by James Wilkinson, who discredited not only Clark but Anthony Wayne and Washington and Aaron Burr, to mention only a few, as a way to clear the path for his own career aspirations.

And speaking of Burr, as late as 1805, when Burr was at both Locust Grove and Clark’s Indiana home, he wrote that he never saw a man of so much natural capacity and general knowledge as George Rogers Clark. So we can be pretty sure that Clark was not a debilitated alcoholic in 1805. Once he moved to Locust Grove, his nephew wrote that either Lucy or William Croghan left a toddy for him on the dining room table every afternoon, and that was his total alcohol consumption for the last nine years of his life.

I think something maybe that hasn’t been considered was the possibility that Clark was a diabetic. He grew increasingly heavy with age; he was known to have inspired fits of rage followed by long periods of mellow reflection. But the most interesting clue comes from the amputation of his right leg that had been badly burned weeks, maybe months, before it was amputated. All that time that terrible burn, which was becoming gangrenous,

apparently gave him no pain, and the surgeon reported that Clark refused all alcohol–the only sedative they had available–and endured the amputation, as he said, better than any man he had ever known. Clark behaved as if he did not feel the removal of his leg. And one last little thing: William and Lucy’s oldest son John graduated from the University of Pennsylvania’s medical school, and his senior thesis was diabetes.

I don’t think he was an alcoholic; I think he had a lot around to drink, as all Western men did, and drank somewhat excessively, but he drank minimally if at all when the circumstances required it. He was choosing to drink; he wasn’t driven to drink. I think had Clark lived 200 years later we would have a different view of his health and his relationship to alcohol.

Q: What did Clark’s men think of him—the ones who followed him to Kaskaskia and Vincennes, or on other campaigns?

Potts: When Clark went to Philadelphia in 1798, and the federal government wanted him to sever his relationship with France, he chose to not do that, and instead sort of slid out of Philadelphia, probably in the middle of the night, with the federal force after him, and somehow managed to get word to a few of his old Illinois Regiment men just as the feds were about the capture him. The men of the Illinois Regiment interrupted the process of capture. Clark was a little slippery in his description of exactly what happened there, but his Illinois Regiment showed up, stopped the federal force, and allowed Clark to get across the Mississippi River to take shelter in St. Louis. This is 20 years after these same fellows captured the Northwest territory for Virginia.

And who’d been camped on the banks of the Mississippi for nearly four years waiting for that French campaign to New Orleans to begin? His old Illinois Regiment comrades. I think most of these men would have—and did–follow him to the ends of the Earth.

Katherine Dalton (Boyer) is a writer and editor, and a former board president at Locust Grove. She is a contributor to Wendell Berry: Life and Work (University Press of Kentucky), Morris Grubb’s volume Conservations with Wendell Berry, and Localism in a Mass Age: A Front Porch Republic Manifesto.