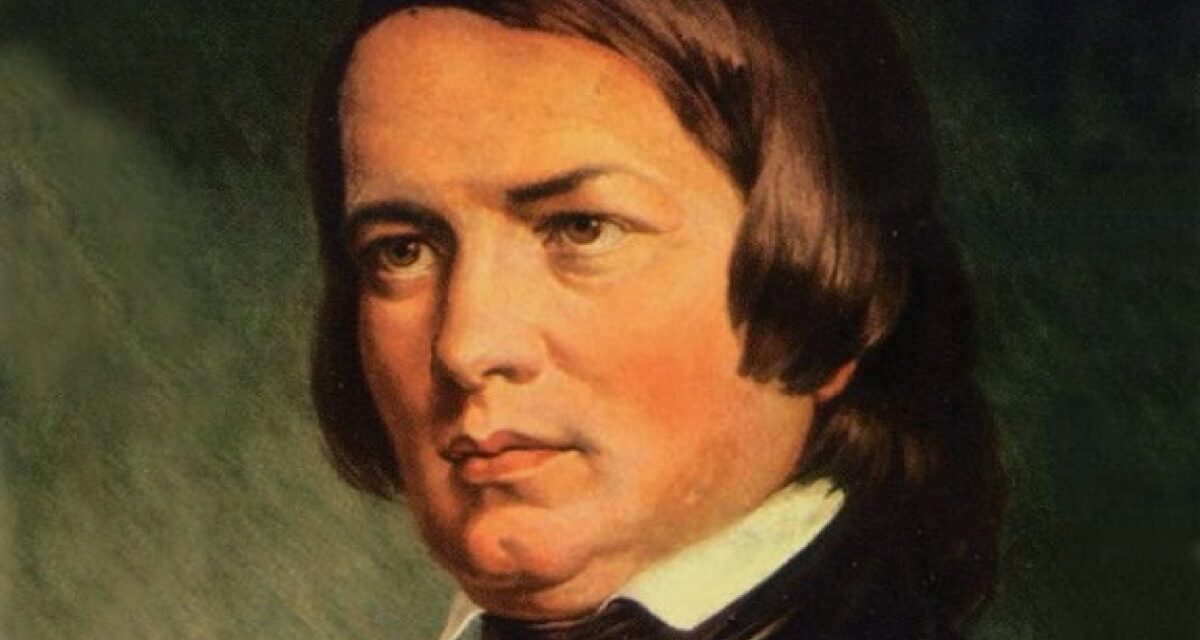

Composer Robert Schumann

Teddy Talks Schumann

Louisville Orchestra

Teddy Abrams, conductor

A review by Annette Skaggs

Entire contents are copyright © 2022 by Annette Skaggs. All rights reserved.

When Teddy Abrams came on as the Artistic Director of our venerable Louisville Orchestra, he brought with him ideas that would help to generate fresh creativity into the orchestral music form, such as the Teddy Talks series where he dives into some of the history and musical theory behind great classical works. For this past weekend’s choice of music, we get a look into the work of Robert Schumann and his Symphony No. 4 in D minor, Op. 120.

Like with many composers and artists, then and now, composition often requires a vibrant and expressive imagination. Schumann’s imagination, perhaps, was a bit more fertile than others, including having make-believe friends. Having lived with mental instability most of his life, Schumann incorporated his mania into his musical work, as well as his writings (he wanted to be a novelist).

Schumann could be methodical when it came to his compositions, often devoting time, energy, and development to specific genres of music at a time. Known for such works as Symphonic Studies, Carnaval, and Fantasie in C, Schumann’s Symphony No. 4 in D minor was actually his second symphonic work, but he brushed it aside and refocused the piece to what we now know.

Mr. Abrams shared with the audience that this piece has so many nuanced notations and musical maps contained within that it takes great concentration from everyone on stage, including himself, to deliver the genius that is scribbled on the staff lines. Everything from the musical directions once in Italian now in German, to the decision to take full stops where a hint of a rest may lay. In fact, while the piece is written for four movements, the notations suggest that it be played more similarly to a fantasy, meaning no discernable stops or breaks. Fortunately, this is interpretive action, in that Teddy allowed for a little breathing room in between the movements. But only for a few seconds.

Realistically I could go on for pages and pages as Teddy delved into the musical theory of the featured piece, but let’s focus on some of the more fun highlights of the discussion.

Built upon descending and ascending thirds centered around a three-note motif, the symphony is deceptive in its complexity, especially as it begins in D minor, as the title suggests, but quickly evolves into a major key, F#. The three-note motif is used throughout the whole piece in different ways; it can be found in solos, such as a violin descant, played elegantly by Gabriel Lefkowitz as well as in a duet with oboe and cello, strikingly shared by Alexandr Vvedenskiy and Nicholas Finch, respectively. Another clever musical tool that our composer embedded was a canon, or echo, of the motif, delivered throughout the whole of the orchestra.

Something about the number three must appeal to Schumann for this arrangement. Other than the three-note motif, which in and of itself is not all unusual, what is strange is that the first note you hear is actually on the third beat of the measure. Yes, that’s a little different.

In the second movement, Romanze: Zeimlich langsam, also known as an exposition section, Schumann wanted to incorporate guitars into the composition, but removed it. Fortunately for us, Teddy reinstated the section and two of our talented instrumentalists, Jon Gustely and J. Bryan Heath, who we normally hear on their respective horns, lent their musical prowess to the guitar to hear what it would have sounded like. I would have liked for it to stay in.

Our conductor shared that he felt that the third movement, Scherzo: Lebhalt, sounded like pirate music. While it sounded a bit grand and perhaps heroic, I had a hard time picturing swashbucklers in the background. But what I did hear was folk music, not just in the aforementioned movement but strewn throughout. Teddy shared that it was not unusual for composers such as Schumann, to incorporate popular tunes and dances from the regions in which lived.

The fourth movement, Langsam, is tricky. In the end, there is a return to the exciting and heroic sound that we heard in the third movement, but it is the course of getting there that is the challenge. Strict attention has to be paid by the orchestra as to what musical cues the conductor is going to give, because, it is all very interpretive. It is written that way. It is also a movement that is the very definition of the use of counterpoint in music.

Teddy shared that he wants each of us to have agency to decide if the piece is working for us. He also stated that he doesn’t expect that we would be able to recognize where exactly within the piece one would be if a needle were dropped on the record, but that we have a clearer roadmap of how Schumann got to where he did on his Symphony No. 4 in D minor road.

Bravi Tutti!!

Teddy Talks Schumann

October 15, 2022

Louisville Orchestra

Kentucky Performing Arts

501 West Main Street

Louisville, KY 40202

Louisvilleorchestra.org

Annette Skaggs is heavily involved as an Arts Advocate here in Louisville. She is a freelance professional opera singer who has performed throughout Europe and in St. Louis, Cincinnati, Boulder, Little Rock, Peoria, Chicago, New York and of course Louisville. Aside from her singing career, she has been a production assistant for Kentucky Opera, New York City Opera, and Northwestern University. Her knowledge and expertise have developed over the course of 25+ years’ experience in the classical arts.