Hollywood’s Golden Age

Louisville Orchestra

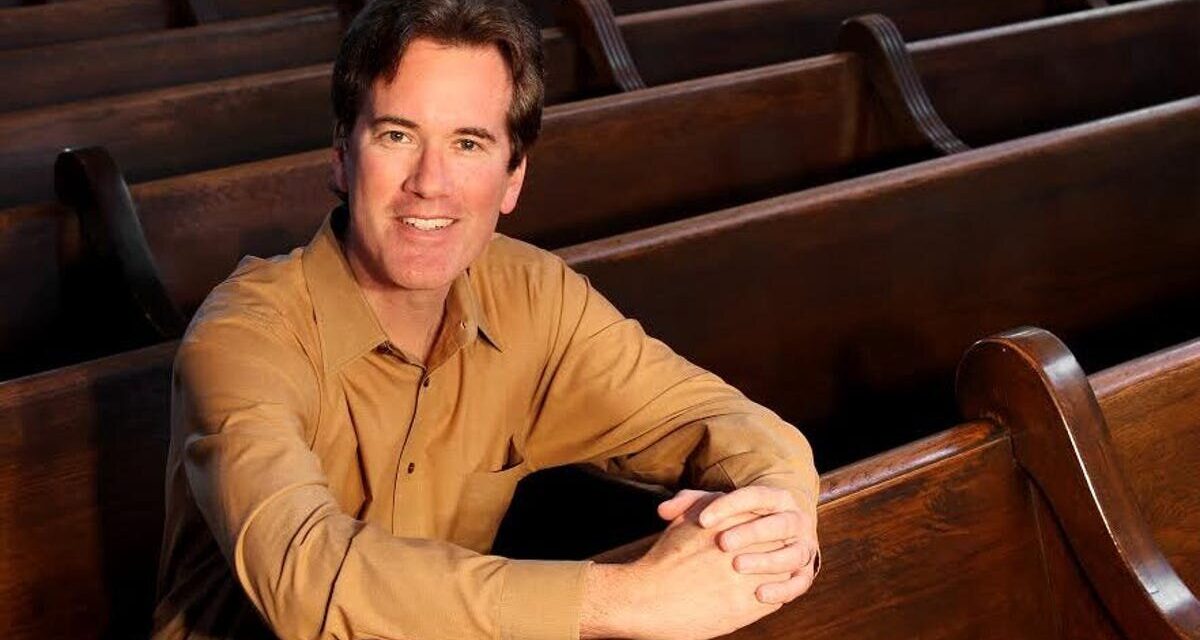

Bob Bernhardt, conductor

Michael Chertok, pianist

A review by Keith Waits

Entire contents are copyright © 2023 by Keith Waits. All rights reserved.

As much as film scores are celebrated, they often recede into the background, reinforcing the action onscreen without calling attention to themselves. In the age of the modern-day blockbuster, bolder, declamatory music came to the forefront of cinema aesthetics, with John Williams leading the way with his legendary work with Steven Speilberg and George Lucas.

Louisville Orchestra conductor Bob Bernhardt is a film geek, a fact exemplified by the nerdy glee he brings to the occasion. So am I, so I laughed at every corny joke. I also respect his encyclopedic anecdotes about each selection. Best of all, he included Themes from Silverado, an underrated score by Bruce Broughton that tidily and joyously references every great western film score that came before.

Yet none of this is the “Golden Age” of the program title. For that Bernhardt offered the sweep and panache of Erich Korngold’s Captain Blood Overture and Max Steiner’s moody Theme from King Kong. Both are sturdy examples of early film scores when the form was still developing, and Bernhardt reminded us that many of the composers from this period were Europeans fleeing the rise of Fascism in the years before World War II, moving from opera and symphonic forms to the Hollywood movie.

Another European emigre, Miklos Roza, is here represented by “Parade of the Charioteers” from Ben Hur (1959) which, although played with flair and intensity, came off to me as one of the more generic selections from this composer. Standard Hollywood bombast.

A choice that better represented the ingenuity and romanticism or Roza was the Spellbound Concerto, which featured guest artist Michael Chertock on piano. The Alfred Hitchcock film is an uneasy mashup of mystery, psychology, and surrealism, but Roza’s music is arguably the best part and the Louisville Orchestra brought out all of the ethereal and enigmatic qualities to be found there.

Pianist Chertok is apparently as much of a film geek as his old friend Bernhardt, but his showcase was the 2nd movement from Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 21 in C Major, famously the centerpiece of the Swedish film Elvira Madigan (1967). The lyrical movement is an elegant aural dance between the strings and the piano, and the performance by Chertok and the orchestra was transporting.

Even better was Chertok’s perfect reading of Elmer Bernstein’s plaintive Theme

from To Kill A Mockingbird, which proves that sometimes less is more when the choices are so apt in expressing the child’s point-of-view.

There was a snatch of the eerie Bernard Herrmann music for Hitchcock’s Psycho, famous for providing no brass, woodwinds or percussion but instead relying on the inherent strain in the strings to emphasize the tension in the story. Yet when the players struck the high-pitched staccato notes from the infamous shower scene, the audience erupted into laughter. Has one of the most terrifying moments in American film become so familiar as to be laughable?

It is well known that Bernhardt is a huge fan and acquaintance of John Williams, and it could said that Williams’ work helps define a new Golden Age of Hollywood film scores, but the first of several selections from the Williams catalog is slightly against the grain of the martial music from Star Wars. “A Prayer for Peace” from his score for Munich is a melodic and emotional piece that echoes some of the motifs from Schindler’s List and conjures some aspects of Klezmer.

Henry Mancini’s Moon River from Breakfast at Tiffany’s felt a disappointment coming so late in the program, well executed but anti-climactic. Mancini’s Theme from Peter Gunn fared better because, as Bernhardt exclaimed, “It rocks!” It featured a saxophone solo and a appropriately pounding rhythm and percussion section. At only 2 minutes, it is over way too soon.

For a finale, Bernhardt returns to his favorite, with an arrangement from John Williams for the Academy Awards entitled Tribute to the Film Composer. It catalogs some two dozen of the most memorable themes from classic movies, including 3 of Williams’ own iconic scores along side Gone with the Wind, Dr. Zhivago, and The Magnificent Seven. It was fun enough and the players really worked it, but again, a disappointing close to the evening.

Except that Bob Bernhardt always has an encore at the ready, the real finale of the evening, and it was music from E.T. The Extraterrestrial, composed by John Williams. With it’s simple, plaintive main theme, through the soaring strings and woodwinds, and closing with the brass and timpani of the mighty climax. The most famous and beloved Williams’ scores are rarely subtle in their overall effect, and he is often accused of excess, but sometimes the overreach is thrilling, and the E.T. suite is a good example of how impactful his music can be.

I found little to critique in the performance by members of the Louisville Orchestra. They sounded exemplary all through the evening. I did wish the Peter Gunn saxophone solo had come closer to the higher pitch of the original instead of staying in the lower register, but that is a minor quibble.

Hollywood’s Golden Age

January 28, 2023Louisville Orchestra

Kentucky Performing Arts

501 West Main Street

Louisville, KY 40202

Louisvilleorchestra.org

Keith Waits is a native of Louisville who works at Louisville Visual Art during the days, including being the host of Artists Talk with LVA on WXOX 97.1 FM / ARTxFM.com, but spends most of his evenings indulging his taste for theatre, music and visual arts. His work has appeared in LEO Weekly, Pure Uncut Candy, TheatreLouisville, and Louisville Mojo. He is now Managing Editor for Arts-Louisville.com.