“BRILLIANT” IN THE NEXT ROOM ASKS IMPORTANT QUESTIONS ABOUT HOW WE LIVE OUR LIVES.

|

|

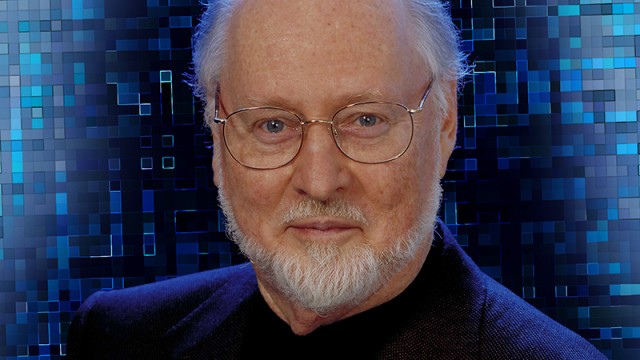

| Cora Vander Broeck and Grant Goodman in Sarah Ruhl’s, In the Next Room (or, the Vibrator Play). Photo by Alan Simons. |

In the Next Room (or, the Vibrator Play)

Written by Sarah Ruhl

Directed by Laura Gordon

A review by Scott Dowd.

Entire contents are copyright © 2012 Scott Dowd. All rights reserved.

Though the title and main gag of Sarah Ruhl’s costume comedy, In the Next Room (or the Vibrator Play), is generated by the work of Thomas Edison and Victorian-era electrical experimentation in general, the heart of Ruhl’s play is more closely aligned with the spirit of Henry David Thoreau and his pursuit of an authentic life.

The Victorian’s suppression of sexuality — especially female sexuality — is well-chronicled in the novels of Jane Austen and the Brontë sisters who were, in Ruhl’s own words, some of her early inspirations. In the Next Room anticipates Freud’s work (at the time of the play Freud was still studying the genitalia of eels at the Laboratory for Marine Zoology in Trieste) but accurately draws on the work of some early practitioners of women’s health inspired, perhaps, by Mesmer’s ideas of magnétism animal published a century before. That is not to imply these practitioners worked primarily for the good of their patients; they were most likely employed by the husbands or fathers of these women to correct perceived imperfections that made them less suitable helpmates — the situation Ruhl establishes as we meet Mrs. Daldry (Cassandra Bissell), brought by her husband to receive treatments for hysteria from the self-obsessed Dr. Givings (Grant Goodman). Dr. Givings uses the latest in electrical stimulation to entice the body’s tides to move and clear the blockages, keeping these sufferers from vigorously fulfilling their duties. Meanwhile Dr. Giving’s own wife, Catherine (Cora Vander Broek), is consigned to the next room and disallowed access to his most interior space. She is becoming increasingly dissatisfied with her own role as wife and new mother.

It is Catherine’s dissatisfaction that gives the play its animus. Simulated masturbation (tastefully hidden beneath clinical drapes) and double entendres are sophomoric in the word’s most literal sense. Ruhl uses this device in abundance to the obvious delight of the opening night audience; but it would have made thin broth without the deeper layers of flavor provided by Catherine and the wet-nurse she is forced to employ (Tyla Abercrumbie). While on the surface the characters deal with the idea of relationship and the oppressive realities of women’s role in the Victorian Era, the essential questions that emerge are more personal, “How do we live authentically? What does that look like? What do we lose in achieving it? Are we willing to make that exchange?” Perhaps most often ignored when considering these questions Ruhl asks, “What responsibilities does authenticity require of us?” A brilliant motif develops in the subtleties of the relationship between Sabrina Daldry (Bissell) and Dr. Giving’s assistant Annie (Jenny McKnight). Many men will, I suspect, experience vindication in its dénouement unintended by the playwright. To say more would be a spoiler, but I encourage men especially to look beyond the obvious elements of this scene.

Ruhl also lifts up the interesting phenomenon no less in evidence today than in 1880 whereby men and women often share space but on separate, parallel planes. While the male characters of In the Next Room carry on their insular lives, making plans and decisions for their wives and dependants, the female characters make connections with themselves and each other that pass unnoticed. Even the painter Leo Irving (Matthew Brumlow), a less impetuous Kirillovich to Catherine’s Karenina, is able to catch only a glimpse of the interior lives of the figures he captures. This idea is restated in scenic designer Philip Witcomb’s beautiful design that incorporates two circles that meet, but fail to intersect. The set is also indicative of Ruhl’s Victorian story-telling style, filled with bagatelles and embellishments often streamlined out of modern theatre. Costume designer Lorraine Venberg’s beautiful, well-made couture has the authentic look of the period without the cumbersomeness that would have made the action of the play impossible. Her solutions were elegant and noteworthy.

In the Next Room succeeds because Ruhl embraces both the absurdity and underlying tragedy of life and offers in the end some hope, yet to be realized, that we may learn to embrace our freedom with a sense of restraint and maturity that might allow each of us to live a more full and balanced life in community.

In the Next Room (or, the Vibrator Play)

January 24 – February 18, 2012

Actors Theater of Louisville

Pamela Brown Auditorium

Third & Main Street

Louisville, KY 40202

502-584-1205

ActorsTheatre.org

Pamela Brown Auditorium

Third & Main Street

Louisville, KY 40202

502-584-1205

ActorsTheatre.org

My husband and I HATED this play! Worst play I’ve ever seen! He fell asleep he was so bored with it :/ And I was glad to see it end. IMO, nothing “tasteful” about it!